Dave Hickey departs for the second time

Art slows life down. Criticism slows art down. They both help.

- Dave Hickey, Facebook post on 11 September 2014

PL

The news that Dave Hickey "quit" writing about contemporary art reached me through his Facebook page several weeks ago: "Okay. My hour's up. Bye bye." It was concise enough for Twitter and an exact repetition of what he had said two years ago, which made it a quotation. The previous announcement was followed by a series of articles; MailOnline posted a long text about the event with an explanation of the reasons stated by Hickey, while The Observer titled its article: "Doyen of American critics turns his back on the ‘nasty, stupid' world of modern art." The British press used the occasion to attack local stars, Damien Hirst, Antony Gormley, and Tracey Emin, which, as it seems now, was futile. Already familiar with Hickey's provocations, the American press was more reserved.

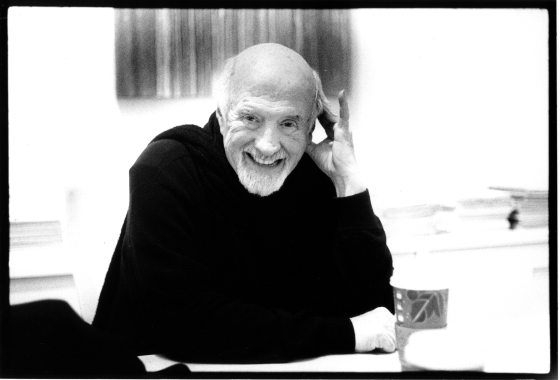

Dave Hickey. Photo.: Toby Kamps

A giant among American art critics leaves the profession, but, extraordinarily, he was neither fired from his position at a newspaper or magazine, nor was he in any way deprived of a space for publication - it was his decision. In his interview with The Observer, Hickey claimed, "Art editors and critics - people like me - have become a courtier class... All we do is wander around the palace and advise very rich people. It's not worth my time." He criticized the contemporary art world, especially its fascination with celebrities, many of whom contribute little to art; Hirst was the most salient example. Some of Hickey's complaints may have seemed surprising, for on many occasions he defended the art market - seeing its lack of regulation as an important driving force behind art.

Hickey was seventy-one years old at the time of his resignation and had had a long career as an art critic. In 2001 the MacArthur Foundation awarded him the prestigious "MacArthur Fellowship," commonly referred to as the "genius grant." He achieved wide acclaim thanks both to his polemical texts on recent art and culture and his very particular style of writing, which is in opposition to the international lingua franca of art critics. His language is rich with vernacular expression - including expletives - and reminiscent of Beat Generation poetry, while his art criticism contains references to both art history and American pop culture, including music and especially rock-and-roll, the music of his youth (he used to write song lyrics and work for Rolling Stone). At the same time, Hickey's writing is full of self-reflection and often ironic, as exemplified by his comment, "Rock-and-roll works because we're all a bunch of flakes." Consciously contentious "anti-intellectualism" gained him the status of an outsider and attracted many readers, both in the United States and elsewhere. Hickey's admirers expected provocative statements and he never failed them. In a 1995 interview, the critic Saul Ostrow called him the cause célèbre of the art world partly because he was not afraid to speak about beauty using the capital B, seeing it as a social, "political" phenomenon. "Beauty's not the end of art: it's only the beginning," he told Ostrow. At the same time, he questioned the role of the critic as a "high priest of art" and, in the same interview, quipped: "I'm a permissive, unfashionable commercial guy. I do retail." In this context, he could be positioned among those American critics who strongly oppose "academic criticism," its requirement to support given methodology, and the kind of writing on art that is nowadays widely practiced in art magazines, exhibition catalogues, and art history books, which, as Oscar Wilde put it, stems from the assumption that "only boring people are treated seriously." He adheres to "popular" criticism that is "made in Las Vegas" (where he lived for many years) and accessible to an ordinary, non-professional reader who does not understand the jargon of contemporary criticism and does not read footnotes. This does not mean, however, that Hickey is not sensitive to the beauty of words or the logic of argument. He is, in total, a critic who records the Zeitgeist while most likely considering himself "a one-man Zeitgeist" (as he once termed one of his favourite actors, Robert Mitchum).

One may find Hickey's provocative statements irritating - and, indeed, many "serious" critics have, in fact, been irritated. The opponents of his style of writing accuse him of using a vulgar strand of "metaphysics," but no one can deny him his exceptional writing skills. Let us quote the following sentence: "They may live in the house of art and speak the language of art to anyone who will listen, but almost certainly the are ‘about' some broader and more vertiginous category of experience to which art belongs-and that we rather wish it didn't" ("Nothing Like the Son: On Robert Mapplethorpe's X Portfolio"). One reads his essays with passion, enjoying each sentence, which, sometimes, does not invite deeper reflection, yet never fully dismisses it. One might say Hickey's writing parallels Mapplethorpe's process; namely, he talks to everyone about the kind of art that few want to know about and about which only few can talk without moralising or unnecessary theorising.

As Hickey stated two years ago, his decision to stop writing about contemporary art was caused by the fact that the art world became excessively bureaucratised, leading to stagnation; the MailOnline article compares this world to the 19th-century salon, which promoted mediocrity, awarded those who had the right connections, and thwarted progress. Indeed, it is hard not to notice the growing institutionalisation of contemporary art, and it is apparent in the fact that the central position in its promotion is occupied by curators, gallery owners, organizers of art fairs, collectors' consultants, and even PR specialists. It is them who decide who is important and who is not in today's art; artists or critics don't have much say here. The often repeated argument that more people view exhibitions of contemporary art nowadays than ever before has very little to do with the real interest in art - attending exhibitions has merely become a "lifestyle." It is enough to attend the Monday evening meeting for young "MoMA supporters" with its atmosphere of a cocktail party and Monet's Water Lilies as mere decoration. "We live in the times of particular emptiness, when everybody speaks about art, but there are just a few who are actively engaged in it," was a comment (quoted from memory) on Hickey's Facebook page. In this respect, the art world has become a lot like the world of fashion, and in the world where glamour reigns, we've come to refer to artist-celebrities by their first names only: Marina, Jeff, Damien - like supermodels, film stars, or pop singers.

Of course, the culture of "stardom" is nothing new among artists. Yet, what makes Jeff Koons different from Jackson Pollock - or even Andy Warhol - is that "Koons, by contrast, has perfected the art of taking the same crap on offer at a big-box store - be it an ordinary pail or kitschy figurines - and making it better than anything you could ever own, so that the buyers of his art might feel superior to the plebs without having better taste than they do," as Barry Schwabsky aptly observed in an article published in The Nation on the occasion of Koons's retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Koons is a reactionary artist who legitimises all that is most shallow and cynical in our culture, an accusation that certainly cannot be thrown at either Pollock or Warhol. Koons' recipe for success is nowadays repeated ad infinitum: provocation, another provocation (preferably one to provoke reaction of conservative segments of society) supported by self-promotion and, finances permitting, an advertisement in one of the major international art magazines. In the contemporary art world, success often translates into the amount of ads in Artforum, which Jerry Saltz calls the "porn of the art world" (and he writes extensively about it in a recent article on New York Magazine's entertainment news blog).

Indeed, the situation of contemporary art, with its cult of celebrities and colourful ads, does not fill one with optimism. However, as history teaches us, artists can effectively break away from the traps of crises, so perhaps one should not prematurely anticipate a new crisis or predict yet another end of art. Whether a similar situation concerns art critics is a different story. To answer this question, one should perhaps start from considering whether a suitable response to the malaise of art criticism would not be to stop writing about celebrities' art, or at least writing about them more insightfully, as well as to direct the readers' attention to the work of less well known artists (not necessarily the younger ones) or those who were unjustly forgotten... As we all know, there are many talents among them.

Of course, art criticism cannot exist in the void and has to react to the interests of the readers and to the Zeitgeist in which we live, as it undergoes significant transformations related to the changes of the media. The role of the critic is being transformed in response. Has he/she really become a "courtier"? That may be so, yet certainly for many more reasons than the ones mentioned by Hickey. (Is it not proved by the situation in Poland, where the art market is still undeveloped, there are very few collectors, and yet there are several local celebrities?) Following developments in contemporary art requires mobility. To get a panoramic picture of the crucial phenomena in art, it is not enough to just observe it from one place: be it New York or London, Las Vegas or Warsaw. One needs to travel around the world and open oneself to new artistic experiences, for, as Hickey admits after all, art criticism has to actively follow art. Yet, when he is constantly expected to vigorously and polemically react to what is happening in contemporary art, he becomes increasingly detached from it; a dynamic commentary is substituted by a "static" reflection, sometimes coloured by nostalgia for the times when there were many artists highly committed to their work. Yet, perhaps, it is not just nostalgia for the art world of the past; maybe his "detachment" comes from his growing disillusion about his own social role...

Hickey's "departure" brings a more general reflection. History teaches us that critics who left a distinct legacy hardly ever considered themselves "art critics;" they simply wrote about art with passion, using lively (and sensitive) language that inspired the readers to further probe the mysteries of art, especially those that seemed very dark. Undoubtedly, Hickey does have this kind of talent. So, perhaps, he should continue writing without calling himself an art critic. After all, he has a singular literary talent, and it's demonstrated by his collection of short stories titled Prior Convictions: Stories from the Sixties. It is where I see the point for his "departure."

Hickey has almost two thousand followers on Facebook (and five thousand friends) who regularly engage in active conversations with him. The success of his page suggests that an informal, immediate communication between the critic and the reader is increasingly popular, and with readers from different generations. In the course of such a dialogue, Hickey's style of writing - a mixture of in-depth reflection with brief comments typical for a diary - gains polemical character, encouraging readers to question the status quo and search for new meanings in art. Like the Internet in general, Facebook often produces unexpected situations, and which Hickey likes to provoke. Although the fluidity of information and comments on Facebook renders yesterday's posts uninteresting, they do not die. One might say they are launched into orbit where they will stay forever. They may be retrieved later and with new meanings not so much as fixed knowledge, but as a constant exchange of ideas posing open-ended, "Socratic" questions on what art is and where it is heading. The immediacy of this kind of communication is, of course, important, yet the most interesting aspect of Facebook seems to be that at the time when popular art magazines, newspapers, or blogs are increasingly dependent on advertising and hence shifting towards providing "neutral" news, or even gossip on art, Facebook (despite the fact that it is closely monitored), becomes a forum for the expression of uncensored opinions. Paradoxically, then, what emerges is a kind of "slower conversation" about art in the form of a dialogue uninterrupted by pages and pages of ads.

Perhaps Hickey's post in question was another "hoax," as some have suggested. But each repetition brings something different (not so long ago the meaning of this phenomenon was the subject of an academic debate between Derrida and Deleuze; numerous philosophers had done it before them, as well), and Hickey skilfully used this repetition to say that he is "quitting" again - and that's it. Does it mean this time that he considers further distancing himself from the traditional model of writing abut art represented by art magazines such as Artforum, The Art Newspaper, or Art press and focus on Facebook? Or, perhaps, does he mean to direct our attention to the fact that since he said it the first time, the art world has not changed for the better, but the significance of social media has increased? Regardless of the implications, it was simply another good post, which I "Liked."

P.S.: "Warhol used to carry this cassette tape recorder around with him. It was always on and Andy carried batteries in his pocket. He called it his ‘wife' and said it protected him. This was because, when the people in his vicinity knew the tape was on, they would forget their anger and unhappiness and try to make a ‘good tape.' I was hoping Facebook would work this way, but...." Dave Hickey, Facebook post on 20 August 2014

Marek Bartelik runs an irregularly updated blog: marekbartelik.wordpress.com