On historicizing Conceptualism and the interpretation of feminism. A conversation with Ewa Partum

[PL]

Karolina Majewska: The recently published bilingual monograph Ewa Partum 1 is a polyphony of voices that avoids proposing a straightforward, unequivocal interpretation of your work. This seems unusual for this sort of publications, which usually tend to inscribe the artist's name into a fixed narration of art history.

Ewa Partum: There is always a certain resistance when it comes to integrating female names into art history; people are rather careful and wary. For instance, in his text, Andrzej Turowski2 is trying to explain why he, or in general, Foksal Gallery circle didn't notice my work at the time, in the seventies.

KM: He mentions talks at the doorstep of the Foksal Gallery.3

EP: It's not actually true. We were all meeting in the gallery space, since Foksal was a very important place for us. However, the only woman who was exhibiting there was Maria Stangret, Kantor's wife, and this was only under his supervision.

Ewa Partum, "Film by ewa - Tautological Cinema", 1973, 8 mm film, black and white with no sound, 4'12''

KM: In his essay, Turowski delineates 'conceptualism of conceptualists' and then positions your work somewhere apart from this movement.

EP. In Poland, during the seventies, avant-garde art was a male-only domain. Even in the late sixties those artists and critics were not aware of what I was doing. A good example of this was my early project Obecność/Nieobecność (Sopot 1965). The male avant-garde artists were completely oblivious that this was the direction in which art would soon develop.

Tadeusz Kantor was a dictator of Foksal Gallery. Wiesław Borowski was trying to impose monopoly on artistic production in Poland. A good example of his attempt at this strategy is provided by an article Pseudoawangarda4 - their dream was to have art world closed and structured by decisions made at Foksal Gallery. They were afraid of a new wave of art, which they could not control; which was free from their protection and management.

At the beginning of the seventies I founded mail art gallery (1971-1977, Galeria Adres, Łódź). I was in contact with artists from the Fluxus movement and many other Western artists. I also published books and catalogues. In Galeria Adres Wodiczko exhibited his work for the first time - together with Świdziński and Włodzimierz Borowski he showed the project Wystawa jednej pracy (One work show). Also Andrzej Dłużniewski had his first show at Galeria Adres. We received letters with the news form all over the world, containing documents and proposals. Even Dick Higgins sent us a selection of books from New York. Despite this, at the same time, Foksal believed it was only them who should have had access to those important contacts...

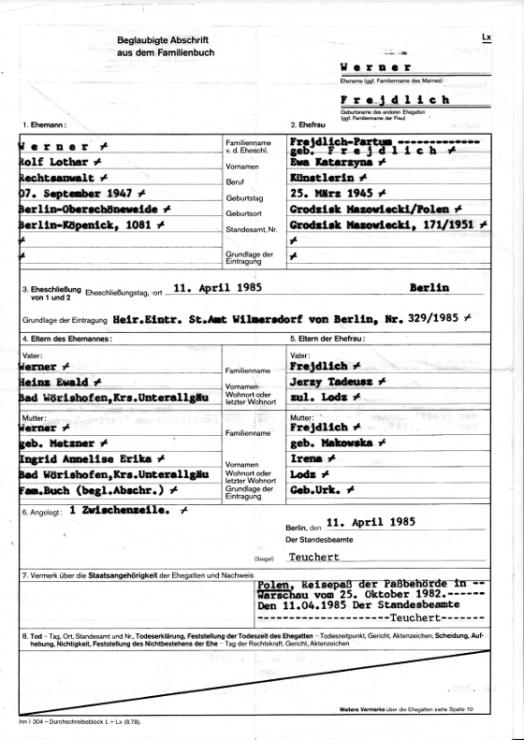

Ewa Partum, „Private Performance" - Marriage Registry Office, Berlin -Willmersdorff 1985

KM: This is why you propose that you should be recognized as 'the first one' regarding some projects, ideas?

EP: At the time museums and galleries refused to accommodate a new generation of artists. In Galeria Adres we wanted to create a space for truly independent art - independent also from local monopolies. That's why I started showing works by my colleagues. Also, it would have been impossible to go to Foksal Gallery and present them my ideas. They would probably have called them ridiculous.

KM: Not so long ago Sanja Iveković said that when she was making her first feminist art projects there were no critics capable of understanding the meaning of those works. There was simply no feminist discourse as such.

EP: Yes, although her career began a bit later, she at least had a chance to be understood. She was also lucky not to have lived in Poland, where, as I said earlier, some critics like Borowski were convinced they knew everything about art and their responsibility was to stop any potential developments that could not be regulated by them. It seemed that the Iron Curtain created perfect conditions for this sort of cultural dictatorship - they felt great power in their leading roles and for many years they were successful with this strategy.

Ewa Partum, "Metapoetry", 1972, Muzeum Sztuki. Łódź

KM: New generations of art historians and art critics are educated within a paradigm of feminist art history and poststructuralism. Don't you think that now your art is becoming an object of some sort of anachronistic interpretations?

EP: This new generation is not so aware of conceptual art from the seventies and is often mistakenly mixing it up with more contemporary critical art practices. I believe it would be of value and very important if a real discussion was initiated.

Ewa Partum, "Active Poetry", Muzeum Narodowe, Królikarnia, Warszawa 2006

KM: But would you expect some sort of unanimous, consistent reading of your art?

EP: Not necessarily - but I would expect an understanding of the situation at the time. Grzegorz Dziamski5 wrote about my art as early as 1980, but even he was not fully prepared. In their interpretations, many critics concentrate on the use of my naked body in my actions without actually understanding that for me it was a matter of creating a sign: a sign pointing into one direction. It was a tautological and not, as so many are inclined to believe, an egocentric strategy. Even in such an extreme situation like in the performance Stupid Woman, where I kiss hands of members of the audience, pour alcohol over my head, write with whipped cream on the floor "sweet art" - in other words act like a drunk and stupid woman - I'm completely in control over my body. My naked body is merely a tool. I'm very focused, not making any spontaneous movements. When the performance is finished I bow towards my audience as a virtuoso after a concert and I say: "Thank you very much. It was a performance".

The role my body plays in my art was very well explained in a text written by my daughter, Berenika, who is an art historian (Text in Ewa Partum 1965-2001, Badischer Kunstverein, Karlsruhe/Muzeum Narodowe). Berenika understood my intentions very well, since she is of course the closest person to me. My point of departure was conceptual art, its transparency and tautology and with the use of this very language I was creating my feminist art.

Ewa Partum, "Active Poetry", Muzeum Narodowe, Królikarnia, Warszawa 2006

KM: You say that you directed your attention towards feminism once you had formulated your own art language. All texts in the monograph seem to deal to some extent with the same problem: how to negotiate your conceptualism with your feminism...

EP: I don't see any conflict here. I have managed to link them together and I have become a tautological feminist sign. Think of one of my works from 1971: my touch is a touch of a woman/ mój dotyk jest dotykiem kobiety. This is a tautological statement - an imprint of my lips. But we can say that this conceptual work has already a feminist subtext. It refers to female language: this impress of my lips is my trace in the language of art.

KM: So, do your works have stabilized meanings? Can the viewer be right or wrong?

EP: The viewer can be right when he/she is able to understand my intentions. Art is a language and if one doesn't understand this language, they can draw quite absurd conclusions. Everybody has of course the right to imagine whatever he or she wants. It is not my intention to forbid or limit anybody's imagination. However, one has to understand the language in which certain statement is constructed.

But if we are creating a completely new language of art (which was the case in the seventies), it is obvious that critics are not prepared and the audience is not ready in the beginning. Also, not everybody is an intellectual and not every artist wants to be a teacher. That's why I believe retrospective exhibitions play a significant role in the process of understanding art. One can trace the genealogy of the artist's language. Sometimes though also critics remain in the position of helpless audience.

Ewa Partum, "Legalność Przestrzeni" (The Legality of Space), 1971, Łódź

KM: The same is probably valid for curators. They impose a net of concepts onto works in order to read their meanings.

EP: In 2005 I have created an installation (Kuratorki. Pomiędzy instytucjonalnością a prywatnością/ Curators. Between Institution and Privacy) which dealt with this problem. In my text, which was part of this work, I explained that curators manipulate art to fit it into their concepts. Their understanding of art depends upon their experiences and upon a particular way of looking at the field of artistic production. It's obvious that not all of them have the necessary intellectual capabilities and intuition.

Ewa Partum, "Legalność Przestrzeni" (The Legality of Space), 1971, Łódź

KM: Maybe it is also a matter of belief that the meaning of art work is created through reading it. Therefore, it is not perceived as some sort of manipulation. In some texts in the monograph their authors seem not to agree with your own reading of your work.

EP: The problem is that conceptual art was intentionally exempted from interpretation. Someone who was not living it, was not related to it, might even not be able to understand this concept.

In case of a conceptual art work its form remains its actual statement. An interpretation should not adopt any external aesthetic ideas.

In the seventies our presumption was that critique as such was irrelevant or even unnecessary. Therefore, we have been writing texts, author's statements etc. in which we were revealing - in a cognitive way - the meaning of our works. These texts are being rarely exhibited together with works - which surprises me. It is impossible to understand a work of art if we don't know in what direction the artist is leading us.

Ewa Partum, "Polityka przemija, sztuka pozostaje", (Politics is Contemporary, Art Remains), Foto Medium Art, Kraków 2009, spreading action of Tadeusz Peiper's poem "Infinitives", photo.: Zofia Waligóra

KM: In 2002, in a response to a text by Izabela Kowalczyk about feminist art in Poland6, you wrote a confrontational letter almost demanding appropriate recognition.

EP: I was defending a certain historical truth. Young people are often not interested in historic dates and therefore it is difficult for them to write an objective art history. Certain things never got through Polish art history.

In exhibitions, I often see works which look very familiar, as if I have already seen them before in the seventies. The problem is that conceptual language of art has not been overcome by any new artistic language.

KM: For sure, contemporary artists did overcome the tautological aspect of conceptual language.

EP: So did I in my later works. That's why I think some people have difficulties with defining my work as a conceptual practice.

KM: There are interesting interpretations of this openness. In her essay, Luiza Nader overcomes a dichotomy between conceptual and feminist practices by referring to a more heterogeneous definition of conceptualism.

EP: Of course. Obviously, I didn't refer in my art to Art and Language. I created instead my own system of signs, which gradually took me further. At some point I wanted to overcome the tautological aspect of language I was using and create works that would deal with reality instead of art and artists. So, I started from myself as a woman.

KM: Let me go back to the question about meanings. Do you think your work can be universally understood without a certain amount of information about Poland behind the Iron Curtain?

EP: My strategy was to be outside of any institutional context; outside of the system. I was young and free from any burden and even any need to collaborate with a gallery to make a work of art. Some of my early works were created in a private context, for instance my work from 1965 'Obecność/ Nieobecność' . Nowadays this is difficult to imagine.

KM: What I mean is that certain circumstances - for instance the lack of art market - influence art practice.

EP: In the sixties and seventies there was a tendency to protect ourselves from the market.

KM: But I suppose it meant something else in Poland and in the West?

EP: We always had the international context in mind. Moreover, some form of art market did exist in Poland. For instance, every year Foksal Gallery sold its works to Muzeum Sztuki in Łódz. The director of this Museum once suggested that he would buy my works if only I made something more lasting. I replied I would wait until he started collecting paper art.

KM: Now your works are part of the collections of Tate Modern, The Art Collection of ERSTE Group and Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid, and also in many Polish art institutions. Does this interest in collecting your work influence the status of particular pieces? Do they transgress form being documentation to being actual art objects? Do you clearly distinguish between documentation and works?

EP: With regard to my films, they are intended as actual works and not as documentation of actions. But in order to present a conceptual installation to a viewer we have to show a fragment of the actual work. Documentation in this case would be photographs showing the whole context. As for the installation Legalność Przestrzeni (Łódź 1971), documentation consists of black and white photos showing the audience, participants and elements of the installation.

In case of ephemeral actions and performances we need to present them in a form of documentation as a video or a cycle of photos. However, there is a possibility that one moment frozen in time can represent the whole work as, for instance, the photo from the performance Stupid Woman.

KM: In your recent exhibition in Galerie M+R Fricke we could see both: the actual works and documentation, but also something in-between. I'm thinking about the work Autobiografia (1971-74), which was intended as an element of performance - a prop.

EP: On the contrary, Autobiografia has become an element of performance. But it was designed as a separate conceptual work in 1971. It is indeed my intellectual autobiography formed from names of famous authors: writers, poets, composers, philosophers - those who formed me mentally and culturally. Later I used this work in my Private Performance (Berlin, 1985), namely my wedding ceremony - a work of art that is at the same time a legal act. This performance has its own document and it has also legal consequences.

KM: But one can say that in Autobiografia you reinforce the male cultural canon. Certainly, this is not a feminist intervention in the history of culture. Why don't you mention any female names?

EP: There were not too many of them. Names of culture makers came from an encyclopaedia and it was indeed a selection written by men. This work was also created in a different context in 1971, when I was still formulating my own language. In this sense, it is not a feminist work of art, but my true autobiography. The biography of a woman who was educated and formed in a civilization created by men. Also in 1974 I've erased one of the names in order to place my daughter's name. This alteration was left visible in the structure of the work. Moreover, all these names are subordinated into a shape of my own name.

KM: Also in your later works you refer to the classical works of literature and visual arts created by men.

EP: We are talking all the time about patriarchate and feminism. My work is not in any case a flirt with patriarchal culture. I understand my actions as initiating a dialogue between two equal partners; as a game between two equal works of art. I'm currently working on a project which illustrates quite well what I mean: I want to use an unlimited issue of Joseph Beuys's Filtzpostkarte and my work from 1971 my touch is a touch of a woman/ mój dotyk jest dotykiem kobiety and create a work of art by responding to Beuys's idea and at the same time by referring to my earlier interests in mail art.

Berlin, 8.03.2014 and International Women's Day and 18.03.2014

monografia Ewy Partum

- 1. Ewa Partum, Instytut Sztuki Wyspa, 2012/13

- 2. Andrzej Turowski, art historian and critic of modern and contemporary art; in the seventies he was associated with Foksal Gallery. The monograph includes his essay: The greatness of desire: On the feminist conceptualism of Ewa Partum.

- 3. Foksal Gallery was founded in 1966 and has for many years been one of the most influential art galleries in Poland.

- 4. The article Pseudoawangarda (The Pseudo-avant-garde) was published in 1975 in "Kultura" periodical by the head of Foksal Gallery, Wiesław Borowski. Anna Markowska writes: "As Borowski's paper made public the transition from modernity to postmodernity, and did it from the position of being modernist, it is a good starting point to show the erosion of consensus of 1955 and a strong need to create agonistic space, which has been characteristic since 1989. Wiesław Borowski decided to fight progressive artists other than those exhibiting in the Foksal Gallery in the pages of an official magazine of a rather dubious reputation to preserve the status of the only legitimate avant-garde. It remains a paradox that a good number of young artists who made their debuts in the 70s regarded this prominent gallery of international reputation as having the ambivalent status of the official gallery. The article "Pseudo-Avant-Garde", discrediting progressive fellow artists, proved to be an anachronistic attempt to resurrect artists' "Thaw" consensus with the government. It turned out that in the communist state there had been no solidarity of the artists, because some of them preferred to replicate the patterns of authoritarian power placing themselves in a privileged and pro-monopoly position. Although the Foksal Gallery opposed the communist state, it adopted some of its tactics and values". Excerpt from: English Summary, [in:] A. Markowska, Dwa przełomy. Sztuka polska po 1955 i 1989 roku, (Two Turning Points: Polish Art After 1955 and 1989), Toruń 2012.

- 5. Grzegorz Dziamski, culture theorist; the monograph includes his essay: Speaking as a woman. Why have there been so few female artists in conceptual art.

- 6. Izabela Kowalczyk, art historian and co-editor of feminist on-line journal "Artmix" (http://obieg.pl/artmix).