From “The Steppes of Europe” to “Ukrainian News”

Zofia Bluszcz: Twenty years ago in 1993 you curated the exhibition, “The Steppes of Europe: New Ukrainian Art”. What was Ukrainian art like at the time?

Jerzy Onuch: I made my first trip as an adult to Ukraine in 1991, just before the fall of the Soviet Union. I was a guest at the time of the First Biennale of Ukrainian Art, which took place in L’viv. I came as a performance artist. Everything seemed incredibly exciting and interesting. Later I traveled with my own performances to Kyiv. What I saw in L’viv was a signal for me not only of an opening, but also of a closing, revealing a reality at the moment of its passage. A new state was formed then, but it also felt itself fluttering in the winds of changing artistic paradigms. The term, “contemporary art” appeared, because in the Soviet period, “suchasne mystetstvo” (the Ukrainian term for “contemporary art”) practically did not exist, at least in the sense in which we understood it. Kyiv interested me when no one knew what was going on there. Thanks to art historian, Halyna Sklarenko, I met the critic Oleksander Soloviev, and through him found the artists’ squat called “The Paris Commune.” That was what today’s Michajlovska Street was called, where I met several artists. Oleh Holosij was an enormous discovery. I spent a day with him, looking at his work, having dinner with him, drinking cognac and chatting with him, I felt that this was a key experience. My second discovery was a meeting in L’viv with Andrij Sahajdakovskyj. These two figures were a kind of challenge for me. After returning to Toronto, where I was living at the time, I began to understand how to digest it all.

Why was the meeting with Oleh Holosij so important?

Because meeting an artist is like a meeting a woman you’ve fallen in love with at first sight. You stand defenseless, because only in such a state can you be open to the world you receive in exchange. Something like this happened with me, when I met Holosij. He burned with an unusual flame. I had the sense that he declared himself as an artist at the same time as he burst into flames as a person. His images were not exactly a formal revelation, painted in haste sometimes leaving an unfinished impression; however, they were a path to a mystery. Holosij showed that secrecy exists as a state, without which our lives would be a banal existence. Researching the history of art, we sometimes come across artists, who know and see that the most interesting thing in our lives is precisely a mystery. Holosij was one such artist.

Ołeh Hołosij, „The Bridge”, 1992, oil on canvas, olej, 200 x 300 cm

The ‘90s marked a new government, a new social order, a time of uncertainty, danger, but also euphoria. How did the artists whom you knew take this all in?

The euphoria from the beginning of the 1990s overlapped for me with the euphoria that emerged during the Orange Revolution among the young artists associated with REP (Revolutionary Experimental Space). I don’t use the term, “REP group,” because it was a large, loose association of about 30 people. I’d rather speak of the idea of the “REP generation.” When we glance at this generation and their first exhibition, we can speak about them all, but not that they had set out a new path in art.

For us it isn’t exactly about new paths, but rather about the fact that these artists function in a kind of reality, are reflecting what is happening in the world.

One may be guided here by the idea of “artistic strategies.” If we try to look at the strategies used by artists during these two key moments, they were repetitions in the formal sense. Suddenly, in both situations, one could see openness, naïve sincerity (a good concept, more and more often starting to be for me a powerful measure of artistic value). A moment of uncertainty as an initial gesture is especially important. In these two concrete situations a pivotal historico-political moment had much greater meaning and it is not possible to ignore this. That’s how it also was with the art at the beginning of the ‘90s. Everything depends on the artists. We have two key figures from two different schools—on one side Holosij, on the other Sahajdakovskyj, and around them I began to build, “The Steppes of Europe.” With the perspective of time this formed for me a certain whole. In the formal sense, the majority of artists drew from a uniform language.

Are you thinking of painting primarily?

Primarily of painting. One of the few people who tried to make an installation was Hlib Vysheslavskyj, as well as the duo of Arsen Savedov and Jurij Senchenko, and also Andrij Shajdakovskyj. The Odessan, Vasia Riabchenko also made an installation strongly connected to his painting. Artists from Odessa frequently connected to the mythology and iconology of the Black Sea region. In general in the painting of Oleksander Roitburd there was a strong connection to mannerism, in Oleh Tistol to historicism, in Holosij to the Romantic tradition, and in Jevhen Leshchenko to naïve art.

Jewhen Leszczenko

It seems that Ukrainian art of the ‘90s oscillated around realism, with a regard for symbolism. Everything had been strictly regulated by the Union of Visual Artists. There was the distribution of materials, commissions, and then suddenly—nothing. Did you then see a struggle with the past, say with socialist realism, a negation of it?

It’s hard to say it was one thing. All these young artists passed through the Soviet system or art education, which trained them in the formal, technical sense. Each of them tried to paint and draw well within academic conventions. I wouldn’t even say in the socialist realist manner. There was rather a socialist-academic form, in which it was not necessary to show the leaders of labor. Of course there were workers painted to order in the so called art factories. There existed decorative art made for the needs of restaurants, cafes, clubs, houses of culture, movie theaters, and they did not need to show elements of socialist realism, but appearing e.g. connected to constructivism.

In the Soviet art. of the ‘70s, for instance, film music composed by Valentyn Sylvestrov and Arvo Pärt displayed their own, complete formal quest for a voice, but within the confines of “functional art,” and not in forms that existed for their own sake, so as not to face the essential challenge or accusation of formalism.

So it was less dangerous?

At the moment of perestroika in the Soviet Union, the genii was out of the bottle. Anyone could express themselves in different ways. In the case of a large portion of young Ukrainian artists, there was the influence of Italian postmodernism, with the transavantgarde of Achille Bonito Oliva. The entire current in Ukrainian art was stamped by Konstantin Akinsha with the slogan, “Iuzhnoruskaia Tioplaia Volna” (“South Russian Warm Wave”). This tied in to the tradition of seeing Ukraine as somewhat separate from Russia, more connected to the south, with the senses, more than with the northern tradition of rationalism. The conceptual tradition practically never unfolded here, though there were attempts, for example the Odessa school that instantly turned toward Moscow. Conceptualism did not “stain” the Ukrainian mentality. There were different and independent figures like Fedir Tetianych. I also met him thanks to Halyna Sklarenko. I don’t know why we didn’t find each other during the project in Warsaw. Maybe he was a bit different, more radical than I knew what to do with or how to find a place for him, and today I regret it, because he was an exceptional figure.

What I found in Ukraine at the beginning of the 1990s was in great measure a refutation of my own tradition.

And what was that tradition?

It was constructivism and the conceptualist current. As a 20-year-old, I learned that painting was dead. Having studied painting for five years in Warsaw at the Academy of Fine Arts, I was occupied with proving that nothing could be done with painting. The appearance at the beginning of the 1980s of “Gruppa” and Leon Tarasewicz, and thus my contemporaries, there developed in me a sense that the death of painting had been announced prematurely. I did not go to Ukraine seeking to confirm my own experience, but I was open to a deeper tradition and reality yet unknown to me. For me the meeting with Holosij was a kind of revelation. In Warsaw at the CCA Ujazdowski Castle I showed only one of his paintings in an enormous empty room, in which one could see a bridge with its own reflection in the water. This was one of his last works before his tragic passing. The news of his death was an immediate stimulus to work on the exhibition, “The Steppes of Europe.”

How did you approach the creation of the exhibition?

The building and creation of an exhibition is a form unto itself. I am close to the tradition of which the unsurpassed master is Harald Szeemann. I like exhibitions that tell a story. For me an exhibition is a little like a stage play, like a film. I approach the assignment like a director, who understands that there are primary and secondary roles, as in the “Immersion” exhibition, that I built in the context of the Polish Year in Kyiv, when the stars were Jerzy Nowosielski and Leon Tarasewicz. Often films are built around the stars, but the Oscars go to the supporting actors, who were Mikołaj Smoczyński and Mirek Maszlanko. When I did “The Steppes of Europe” the main star for me was Hołosij but fine roles were played by Sahajdakovskyj and Tistoł, and the less well known Leshchenko i Vysheslavskyj.

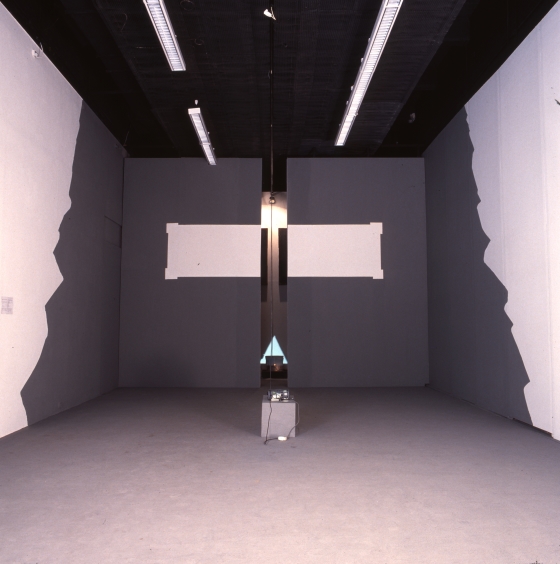

Hlib Wyszesłwski, fragment of installation, 1993

What were the nodal points? The title, “The Steppes of Europe” is particularly attractive, joining the image of wild, romantic, unbridled Ukraine with the European vector, unified in a greater whole. It carries many meanings under the surface. The last book published about Nestor Makhno is entitled “The Pirate of the Steppe.” Here I would also look for the echo of Mickiewicz, “I sailed out onto a dry expanse of ocean…”

This process of return from one side and reception from the other is not yet finished. It’s not just about the European aspirations of Ukraine. Europe has its own steppes that it would prefer to forget about, both literally and figuratively. The idea of the steppe can carries a lot of weight for Ukrainians and for Poles. One could also use the idea of the periphery of Europe. The art of that era was dictated by the need for transgression. We are somewhere, we are on the periphery, we understand ourselves through this peripherality. When we see Sahajdakovskyj and his constant digestion of the provinciality of L’viv, it is necessary to recal that this is a province of Europe, and not the provinciality of Irkutsk or Luhansk. This is a forgotton, abandoned European province. Sahajadakovskyj perfectly understands “fallen” matter and only a proper understanding converts (sublimates) it in its quality.

Andrij Sahajdowski, installation 1993

Sahajdakovskyj’s image with the title “bez zupy ne ma obidu” (“without soup there is no lunch,” which is the main meal of the day in Ukraine), flows from figures that speak in common phrases and very much want to stick to the ordinariness of everyday life, but have within them total chaos and emptiness. It’s as if all hell broke loose during the lunch break.

There is a beautiful, mythologized Habsburg province, in which a political and cultural catastrophe took place. What can one find in this painful reality? In “The Steppes of Europe” there was the important work of Sahajdakovskyj. He created a room scattered with old books, German, Polish. A grammophone was playing some old Austrian melodies in a loop. The walls were painted with red grape juice that quickly began to give off a musty odor. He poured warm water with a substantial amount of sugar dissolved in it over the floor. On one wall he placed a crucified table, very crudely fastened to the wall with some kind of metal bolt. In the middle of this sticky floor his famous three-legged stool that threatened to fall over. Instead of fourth leg it had a very delicate construction of twigs and pebbles that nonetheless tried to stand. It was a sculpture of a mutilated milking stool. This was a very strange space. In the middle the only source of light was a 40-watt light bulb. Many threads to be pulled, a multitude of stories. In Sahajdakovskyj I was drawn to the fact that he tried to grasp the moment of the collapse of the world, and it was as if he tried to place it in a state of very dubious balance. Once my wife had the fantastic dream of moving to L’viv, and he replied, “You can’t live in L’viv, because here, to be able to exist, you have to jump and be suspended in space.” Borys Michajlov, who recorded the collapse of Eastern Ukraine with its homeless, played a similar role.

In Michajlov, both the homeless and the landscape are put on display, sending a signal that people, that buildings (to the extent that it is possible), have the sense of being watched, sending a signal. Sahajdakovskyj is at the same time inbred. In the worlds presented, Sahajdakovskyj speaks of the creation of prostheses, of a precarious psychic balance, but Michajlov shows an absence of desire for balance, and only some drastic, not even desperate, but fundamental hopelessness or inadequacy.

Sahajdakovskyj has been sitting on the margins for many years, the oligarchs not interested in buying his work beyond collectors from abroad. He attacks the Ukrainian nouveau riches, showing that the reality that they have built for themselves is neurasthenic and very precarious. Today they are rich, but tomorrow, with all their unbelievable possessions, they may not be. If the new reality is a fleeting illusion, all the more that they should drive the previous reality into oblivion. They have no time for sentimentality.

Where does this madness for contemporary art as a lifetyle among influential people come from? Not literature, nor theater, nor music, but particularly contemporary art serves as evidence of being “in style.” Looking at the development of institutions, the new foundations most frequently associated with wealthy individuals appear to be within this sphere.

This requires some thought. I have some intuitions. I feel like one of the people responsible for this phenomenon. What we did at the Soros Center for Contemporary Art was an attempt to transplant liberal western values and mechanisms for the dissolution before our eyes of the authoritarian Soviet reality. We were implants. Of course new, of course colorful, and very proficient in producing new models within the arts and for the function of art. Then I believed that I was a modernizer, who understood and felt the needs of Ukrainians. I connected with many of them, but it also happened that at least as many differentiated themselves from me. Of course a “transplant” can be painful. One can prepare the ground, plant one, two, three trees, nurture them for a long time, and after some years, we can have an orchard that bears fruit. One can also plant mature trees to speed things up, but the cost of such an operation is greater. One can also bring ripe fruit, which is general the fastest method, but then fewer and fewer people understand and know how to take advantage of the knowledge of the relation between the apple and the seed.

Walentyn Rajewski

Who would have expected that the garden of contemporary art in Ukraine would be so productive?

I created the Center with the naive romantic belief of a revolutionary, who is convinced that he can only do good. But later, on the foundation that we built, there appeared the phenomenon of Viktor Pinchuk, who, nota bene, was first exposed to the newest Ukrainian art at the exhibition, “The Ukrainian Brand” at the Soros CCA in 2000. Pinchuk created himself, with the help of western PR experts, as a real European, who is occupied with the things that should occupy the most powerful Europeans: the establishment of charitable foundations interested in art. In the case of Pinchuk, the choice fell to the modern art that is called with an English name in Ukrainian, “contemporary art.” But the art that interested this enlightened oligarch was from the ten or twenty most well known and most famous names variously associated with the “top 10.” He put an enormous PR machine into motion toward this end. This was the flywheel that created the present interest, and was relatively easy to do.

I called this the “Dubai Project,” because with the appropriate means, one can create such a situation in the desert, the symbol of which is presicely Dubai. This didn’t happen with the deep forethought and planning, that art, culture is an element for building civil society, as in the case of Soros’ project. Both represented instrumental approaches to culture and to art. They had utilitarian goals. One tended toward building civil society, the other toward the building of his own position as a member of the European elite. The PR agency sent out invitations according to specially created lists—the splendor and taste of the wider world. White Cube and Gagosian were the main suppliers of art. Today the main heroes of the Pinchuk collection --Damian Hirst, Jeff Koons and others are flying out Gagosian Gallery. Gagosian is regarded as a gigantic symbol of corruption corroding today’s art world from the center. And this fits perfectly with the all-encompassing corruption in Ukraine, and is thus accepted with no pain or particular reflection, but only as the lifestyle of the new elite. The price doesn’t matter. The art market is completely corrupt

What does this corruption depend on?

Prices are inflated beyond what any living artist has every achieved. The huge money that’s appeared here, crowds of oligarchs are eager to buy more and more expensive than the competition. There isn’t so much great older art on the market, and the money available to be spent is enormous. So what’s left on the market is contemporary art. Made yesterday, sold today. Each year its price grows at auction—manipulation, the destruction of standards, anything goes. It’s not that there isn’t interesting art. It is still produced, but is traded in a horrible manner with no rules—with no civilized rules.

You lived in Ukraine for thirteen years (1997-2010), and have observed it for twenty. How do you see the changes from the beginning of the 1990s to around 2010 among the artists? What interests them? How would you compare these two periods?

An inherent element of reality in Ukraine until today, and this also concerns art, is a certain schizophrenia. The causes are many. For example, take Sasha Roitburd and his status as a major providor of mainstream art, mainly painting.

Ołeksader Rojtburd, pictures from cycle „Lady in white”, 1993

Once he built his position as a searching artist, very intelligently using video with his own materials as well as what he could borrow. That was his famous work on the Odessa Steps: “The Psychological Invasion of the Battleship Potemkin in the Psychedelic Vision of Einstein” found today at MoMA. For me that Roitburd is an original, important artist. What is happening with the younger generation, with social and artistic activism on one side, and right afterward shaking the hands of the oligarchs and the production of work that can find buyers on the weak Ukrainian market. We may also say that this is an example of the diversity of attitudes. We have something for export and something for the internal market. The goalposts are short. I understood rather late that the Germans who created the Mercedes achieved success not because they were trying to impress someone, but only because it emanated German values. Ikea enjoyed success, because it came from Scandanavian customs, traditions, which managed to infect millions of people around the world. A physical product may be exported, but it carries the essence of the group that gave birth to it. This is not at all a matter of “national spirit,” but of some kind of spirit in general, a mystery that is contained in that spirit.

Trans. David A. Goldfarb

Photos of exhibition “The Steppes of Europe: New Ukrainian Art” in CCA Ujazdowski Castle (Warsaw, Poland, October -November 1993) by Mariusz Michalski & Barbara Wójcik.

March 15, 2013 at 6 p.m. opening of the exhibition UKRAINIAN NEWS in CCA Ujazdowski Castle

ragment of exhibition “The Steppes of Europe”, on front pictures by Wasyl Bażaj