The phantom enigma, or how to discuss ghosts seriously

PL

Jan Woleński once said "ghosts are ghostly". The book containing this sentence teems with similar bold and hilarious aphorisms which superciliously aspire to become the vanguard of atheism, which is perceived by some as the crowning achievement of rationalism. We must remember that from a strictly philosophical standpoint, atheism and theism are equally justified. This, however, poses no obstacle for Woleński's resorting to mockery, while dressed in the robes of scientific objectivity in order to hijack the truth for one side of the argument only.

But why do we need such a highfalutin adage if we want to talk about art? The analogy is certainly not simple. Jan Woleński would be surprised to find out how much his statements are no longer au courant in reference to painting and modern art in general. This is not the right place to recall all the events, exhibitions or individual works which evoke ghosts and nightmares, which locate us in the realm of Holy Mass, religious ceremonial or spiritual séance, which research forbidden books, draw on secret knowledge or conjure up visions of the end of the world that are either enticing or frightening. However, what we can state for certain is that we're dealing with a worldwide trend which has been recognized by art critics. An interesting point is made by Nicolas Bourriaud who notes in the introduction to the Polish edition of his Relational Aesthetics: "Many representatives of artistic circles believe that we are witnessing the dawn of a new era (...) the emergence of esotericism which uses its deliberate elitism in order to supplant the negotiated dialogue forms and the practice of democratization of the work of art - both of which dominated the art scene of the 1990s. Mystic truths - an exhibition organized by Natasha Conland in Auckland (July - August 2007) - delved into analogies between an artist and a visionary or researcher of the unknown (...) At the same time the sixth issue of the British magazine Garageland was devoted in its entirety to the "supernatural", including spiritualism, shamanism (...) the paranormal and the Victorian gothic. The same phenomenon could be observed in Paris, where the largest rooms of the Pompidou Centre were adopted for the purposes of the exhibition Traces du sacré, which penetrated into the relationships of some 20th century artists with religion"1.

As it seems, these phenomena which appear in art worldwide, also find analogies in the Polish artistic demimonde. In either case they have their roots in the entire sphere of social life which the artistic trends - forgive this naive Stendhalian realism, but this is what such "ghostly" discussions demand - reflect. Briefly speaking, we are living in a time of political and conventional conservatism. From fashion and design inspired by decades-old models, through "retro" trends in mass culture and the currency of traditional techniques of food production, to an increase of conservative attitudes in politics, we are witnessing a growing interest in all things past. Adding spice to the matter is the fact that the attempts to tame, appropriate or rewrite the past often take an unexpected and - it must be said - obscurantist turn.

Therefore, the question of the present-day flowering of esoteric trends is in fact a question about our attitude towards the past - and primarily towards the tradition of the Enlightenment and its legitimate child modernism. Such understanding of this phenomenon may lead us to wonder why the disillusionment with the ideals of modernity clearly makes us squander these ideals or "throw the baby out with the postmodern bathwater"2 as it was bluntly put by Jürgen Habermas as early as in the 1970s. An excellent example was the one-minute silence during the December 2011 session of the United Nations General Assembly - being the flagship achievement of the modernist - to commemorate the death of Kim Jong Il.

So what's happened to the spirit of criticism? Why did it drift away, as if scared of the idea of progress? Did it overlook the fact that the technologization of life also has its emancipating aspect, that the process of subjugation has, in fact generated the ideas of human rights and civil liberties, that the wasteful exploitation of natural resources - an undeniable fact - has also led to scientific progress? Whatever our assessment of the consequences of this enlightened rationalism - whether we focus primarily on the emancipating potential of this cultural formation, or take the opposite approach and emphasize its reifying and totalizing character, it is certain that we have reached an impasse (a state as indefinable as spirits - creatures that are neither alive nor dead). The disillusionment with the idea of development - at least in its two extreme forms offered by modernity - i.e. capitalism and socialism - has led some to seek good fortune in esotericism and occultism. Those who do seem to have forgotten that it is as easy to go astray as it is to find hope in these areas.

On the other hand it may seem unnecessary at this point to resort to pathos or strike an apocalyptical note. While painting a black picture of reality, Bourriaud himself admits that occultism "is a double-edged weapon. It offers tools which legitimize pro-fascist behaviours, and yet at the same time it echoes the idea expressed in Marcel Duchamp's prophetic dictum: »The great artist of tomorrow will be underground« (...) The present-day return of the "irrational" is not necessarily tantamount to political capitulation, as long as we are not lured into vulgar mysticism. That which is irrational also has a potential to destabilize reality"3. He also adds that it is necessary to consider "what, in the new aesthetic climate, can be regarded as regression, and what as reconfiguration, i.e. an attempt to rework the form from a new point of view"4. In other words, before we pass final judgement, we must find out who is conjuring up ghosts and what ghosts are being summoned.

So why did Siggi Hofer and Marcin Maciejowski decide to show their work at an exhibition called Phantom? Maciejowski lures the ghost-figures of some classic masters of Polish and world painting. On the other hand, Hofer, who reaches for the past in a less ostentatious way than his fellow Polish artist, once evoked in his works the spirit of the traditional culture of the borderland between Austria and Italy, and now for the purposes of this exhibition he creates an alter-ego phantom. Since every ghost comes from the past, every spiritual séance is, by definition, conservative in character. To this effect painting - and perhaps the entire iconosphere - by principle shows phantoms. According to André Malraux, the entire realm of painting belongs to an imaginary museum, or in other words to a strictly immaterial legacy of the past. Therefore, the question of ghosts is first and foremost the question about the past and history, and the spirit evoked through painting is quite naturally, the spirit of tradition. And yet, there are clear distinctions in this asphyxiating world of phantoms - ghosts may appear either as protective spirits or as eerie spectres.

Incidentally, the inclination towards history and the past - which seems to result from the assumption that the present is not given to us directly, but that it is mediated and secondarily coded by the past - is the main feature of Polish visual arts of the last twenty years. It provides fuel for many works, and the reconstruction and rewriting of history constitutes its primary modus operandi. One might speculate that this tendency is the predominant feature of the entire Polish culture after 1989 (Przemysław Czapliński, among others, holds a similar view in reference to literature of the period5). Whereas this constant peeking into the past is a condition for constituting an identity, both at an individual level and on the platform of social life, it is marked by binarity which - one might speculate - is of a generational character. The generation of artists who made their debut in the late 1980s and early 1990s treat the past grosso modo as a reservoir of source experience which, through the work of the collective memory, mass media and education, is interwoven with both individual and collective identity. Also, this identity must be reworked if it is to be noticeable and understandable. Therefore, when Polish artists, such as Artur Żmijewski or Zbigniew Libera explore themes related to the Holocaust, the reconstruction becomes a kind of psychotherapy, a secondary reworking of the trauma. Meanwhile, the generation of artists who are a decade younger follow the postproduction strategy characterized by a free or often even "playful" use of historic themes which, detached from the original context become a part of a visual patchwork, and consequently lose their "gravity" entirely. Although reconstructions offered by Robert Kuśmirowski and Paulina Ołowska, as well as collages by Jan Dziaczkowski feature numerous political threads, these are completely devoid of their ideological world-view function. Instead, they usually play the part of visual gadgets, interwoven into a witty context.

One might venture the statement that this provisional division into art which seeks source experience in the past, and art which sees the past as a reservoir of themes drifting freely on the sea of imagination and tradition, has an international reach. Although this generational distinction becomes blurred because the development of art outside Poland is determined by different conditions from those inside the country, these two opposing approaches to history are constantly present. The former embraces reconstructions of historical events undertaken by such artists as Jeremy Deller and Jochen Gerz, wherein the past is perceived as a source of truth and knowledge, and as a point of reference. At the other end of the spectrum are ironic "mosaics" of historical motives evoked, among others by the group Little Warsaw, Christian Mayer, Collier Schorr.

This allusion was intended to show that any model of art which is focused on researching the past includes elements which make our relationship with things past acquire a cognitive aspect and head for the future. This criterion becomes exceptionally useful in the context of Bourriaud's proposal to analyse every work from the standpoint of the past; to ask whether the work alludes to the past, while probing at the same time into the present, and whether it allows us to define tasks facing us in the future.

In the light of this postulate, it seems apparent that we only begin to talk about ghosts seriously if, while practicing witchcraft, which contemporary art is often tantamount to, we see not ghosts, but problems and moot points, as well as solutions to them. Therefore, if we are to become interested in the world of phantoms, it should appear to us as a new and wonderful world, as a world for building, for discussion, for transformation, and finally, for living in. Because, as I have already mentioned, spirits are divided into two kinds - the protective ones, and those who belong to the realm of eerie spectres. The former (also joined by the spirit of criticism) come to help us address problems and find our bearings in the maze of events. The latter lure us into their own world while obscuring reality and its problems. We must therefore decide which spiritual séance we choose to attend, and which medium is likely to cater for our needs.

Translated by Jarek Fejdych

„Fantom", Siggi Hofer & Marcin Maciejowski; curator - Goschka Gawlik, Galeria Bielska, Bielsko-Biała, 23.06 - 26.08. 2012.

Photographs courtesy of Galerie Meyer Kainer, Viena.

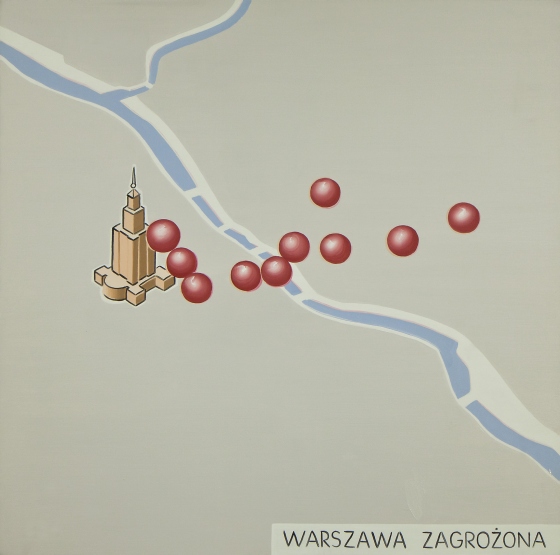

Marcin Maciejowski, Warszawa zagrożona, 2010, 110x110 cm.

Siggi Hofer, BAR ROMANTICA, 2012, Din A4, kredka olejna na papierze.

Siggi Hofer, Fantom, kredka olejna na papierze, ramy, 152 x 152 cm.

Marcin Maciejowski, Why do you devote, 2012, olej na płótnie, 150x100 cm.

Siggi Hofer, Bar Romatica, 2012.

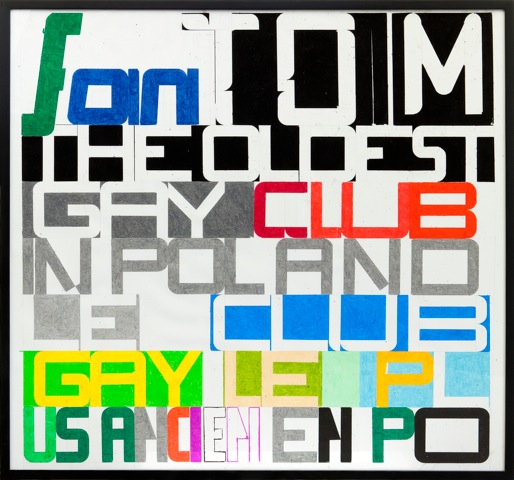

Marcin Maciejowski, An artist doesn’t care about, 2012, 130x170 cm.

Siggi Hofer, Nr 7. No Hole, No Mouth, No Hand, lakier na płycie pilśniowej, każdy 80 x 100 cm

Siggi Hofer, Voyage, 2012, drewno, metalowe kółka, lakier, linka, dł. 112 cm, wys. 42 cm, szer. 25 cm

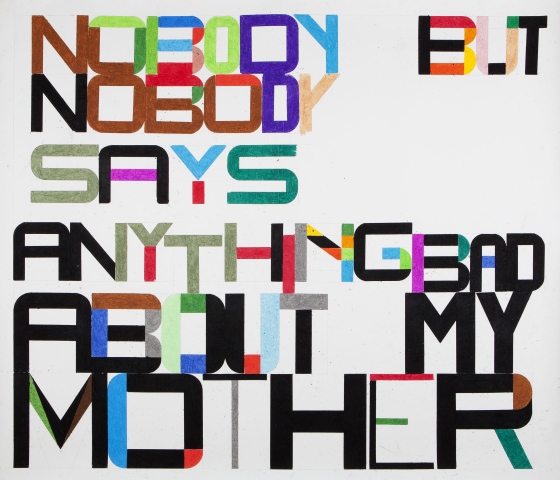

Siggi Hofer, Nobody, 2011, kredka olejna na papierze, 150 x 175 cm

Siggi Hofer, Von Farnen umwachsener Würzelstock, 2009, kredka na papierze, 152x190 cm

- 1. Nicolas Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics, translated into Polish by Ł. Białkowski, MOCAK, Kraków 2012, pp. 10-11.

- 2. Jürgen Habermas, Modernity: An Unfinished Project, translated into Polish by M. Łukasiewicz [at:] Postmodernizm: antologia przekładów, edited by R. Nycz, Kraków 1996, p. 35. A well-known text in which the German philosopher enters into a polemic with postmodernism which he perceives as oblique conservatism and as the squandering of the enlightenment project to improve life by the ideas of rationalism.

- 3. N. Bourriaud, op. cit., p. 12.

- 4. Ibid

- 5. See: Przemysław Czapliński, Język historii in: Historia w sztuce, exhibition catalogue, MOCAK, Kraków 2011, pp. 49-73.