Cool Water and Swedish Scandalist

Debate on provocation and scandal in contemporary art held on the 19th November 2011 at the CCA Ujazdowski Castle, featuring Martin Schibli (curator at Kalmar konstmuseum), Oscar Germouche, Kaia Pawełek, Kamila Wielebska, Zuzanna Janin. Moderator: Agnieszka Rayzacher. The audience profited abundantly from the occasion to exchange opinions. The discussion took place one day after the opening of the exhibition of young artists from Sweden ("Cool Water"; curator: Martin Schibli, artists: Oscar Guermouche, Elin Magnusson, NUG, Anna Odell; lokal_30, 18.11.2011 - 13.01.2012)

Martin Schibli: First we have to think about what actually an art scandal is and what makes it scandalous. You know, there are a lot of scandals in the art world, about who is appointed the director at an institution. But the scandals of this kind are more inside the art world. I think that a scandal is something that also people from outside the art world react to. And I will talk about this kind of scandals in Swedish art. When we are talking about provocative art in Sweden, it's impossible not to mention Lars Vilks. He's the artist who has been carrying out an ongoing project since 1980 on location in the south of Scania, southern province of Sweden. Te artist went there first in 1980. It's very hard to get there, in fact only by boat. Vilks was swimming but suddenly he went too far off the coast and almost drowned, but somehow he managed to make his way back. That summer, he started to build constructions of driftwood - that's how the sculptures Nimis and Arx came into being. It took two years before anyone found out. The authorities became interested in this, and there was a problem of permissions. So first they said the buildings should be destroyed but eventually everything went to court. And the trial has been going on for 25 years. Even at the supreme court.

Lars Vilks, Nimis 1980

There are a lot of different angles to the problem. In Sweden, nature is extremely important and it is extremely important that everyone has access to nature. We have a law that says you need to be able to walk through private areas. So you can't buy a lot of land and then say you have it only for you. In this case, people were upset because Vilks was actually using public area for his private purposes. At first, he didn't have a clue why he was making those objects. After a while, he understood that the struggle with the system was very interesting, so he had to learn how it worked.

The interesting thing is also that after 25 years it is the one of the most popular places to go in this area. Every year 40 000 people get there, people go to marry there, you can also see the place mentioned in erotic novels. At first, the people at the local tourist information office didn't want to say how to get there, but later they just started handing out a map. The place is now loved by people.

And the artist learned his lesson from the scandal - he learned how the media works.

P Hollender, Buy Bye Beauty, 2001

That's another work, it's Pål Hollender, Buy Bye Beauty. At the time it was made, a lot of Swedish companies operated in Latvia and used its cheap workforce He wanted to do something with it. So he got money from the Swedish film institute to go to Latvia and make a documentary about that situation. The documentary is one hour a long, where the first 55 minutes is about explaining the political and economic situation, interviews with businessmen, who admit they appreciate Latvian women. At the end of the documentary, the author buys sex from six women that he interviewed earlier, who worked for the best of companies. And that was extremely provocative to the Swedish audience, because he used government money to have sex with those women. A media hype started after one of the channels broadcasted parts of the documentary.

And there is also Elisabeth Ohlson Wallin. She is a lesbian and a famous photographer in Sweden for portraits - she even portrayed the king and queen. In another project, the artist came up with photographs based on the Last Supper. She photographed her friends - lesbian, gay and transvestite.

People hated her. The interesting thing is that it wasn't even the church, but the ordinary people. Not because it was religious but it was highly homosexual, even though we fully accept homosexuality.

The exhibition went to several Swedish cities and everywhere it was considered disgusting.

I will now mention once again Lars Vilks to talk about the scandal with the drawing of Muhammad as a roundabout dog. Some time ago the Swedish took up a custom to set hand-made dog sculptures at roundabouts, and this was how Vilks presented the prophet in his drawing. Obviously, it triggered an international scandal and earned him a death sentence from Islamic organisations.

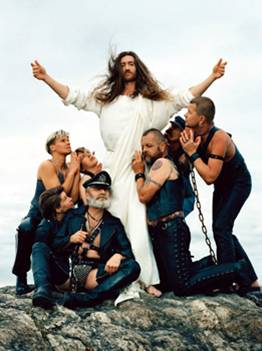

Elisabeth Olhson Wallin, Ecce Homo

Vilks is an artist, but he is also an art theorist, a professor. One of his ideas is to test where the limits of the art world are. Because he denies the idea that the art world is free. The drawing had been shown at two exhibitions, with not much of a reaction until one of the journalists asked the curator: "Isn't it forbidden to make drawings of Muhammad?" Lars Vilks got national attention, he was in all newspapers. In Sweden, Muslim immigrants are considered a weaker group, which should receive support and not criticism of their religion. A lot of fuss was made, the work was taken off the exhibition, and Swedish art institutions refused to exhibit it. And there was also the problem of publishing the drawing in the press. Some newspapers didn't want to print it not to upset the readers, while others said it was very important that people see what was discussed. One of the papers chose to publish a photo of another newspaper with a photo of the drawing in it. Typical Swedish way of solving things.

Oscar:

My name is Oscar Guermouche. In my practice I focus on the social values of words. What I do is that I copy pieces of existing texts and I paste somewhere. I displace texts. I work with texts.

When I was at Konstfack, I considered myself as more or less a star of this institution. The thing is that I wanted to have it on paper, written in black and white. You could actually do that because there was a special grant - each year one student out of all graduates gets a distinction and a grant of around 25 000 zl. When you get diploma like that, you really are the best, and I badly wanted to be the best.

At the last year of studies you develop your own project and you have a solo show where you present the project, and you also have a group exhibition with all other students. My project was based on tattoos. I still worked with text. I'd find a piece of text and copy it on my own body as a tattoo. That was my final exam project. No one else did such a thing, and I knew this would make it. I knew when the teachers and professors would have their meeting to decide who should get the grant. So I planned my solo show exactly before the meeting. I though they would go to my show, and then to the meeting and would surely decide that I should get it. But then suddenly Anna Odell came. She had her studio next to mine, maybe I'd seen her five times, and suddenly everyone was looking at her. I was like "what the fuck?" What about me?" And then Nug came along, he wasn't even a student, he graduated before, and everyone was looking at him. It was dramatic!

I was getting desperate. I wanted the money, I wanted the diploma and I wanted all eyes to be on me, but everyone was looking at them because of the scandals connected to their works. Ok, so I needed a scandal. I knew that the head of Konstfack got quite upset already because of Anna Odell's case, and with Nug everyone hated Konstfack even more. The university authorities knew they couldn't handle another scandal. And they said that you couldn't present at the individual nor at the group show any work made in illegal way.

That's funny, how can you even tell? I mean, if I take a picture and edit it with pirate software, is the art work illegal?

Apart from the tattoos, I also had another project. Martin Schibli exhibited it in Moscow in 2008. The work consists of three flags with pasted lyrics of Swedish regiment marching songs from the times of wars with Russia. The songs are very literal and brutal. In Moscow everyone felt offended. And it was exhibited again by Martin in Kalmar. People were also upset there. Someone threatened to burn the museum, one of the guides refused to talk about the flags. I started reading the law and found a sentence which said that it was illegal to put texts on the flag. That's because when the king would go out on a boat, there had to be a special flag on the boat with a special symbol on it, so that people know that this was the king. It was said that nobody apart from the king could use that symbol nor place any symbols or inscriptions on the flag. And I decided to copy these words onto a flag. When I saw that one of the professors was looking at the text on the flag, I told him that was my work for the spring graduation show. The news quickly reached the university authorities, and they didn't want another scandal. So they banned the work from the spring exhibition. The press immediately took interest in that case. People already hated Konstfack, so I was the good guy and Konstfack was the bad guy. Everything went back to normal. Interviews in every newspaper in Sweden, sitting on a comfortable sofa all day, talking to journalists. The authorities of Konstfack realised that if they wanted to avoid another scandal, they should allow me to show the work at the exhibition. Of course I also got a diploma with distinction and the grant.

Oscar Guermouche, Chcemy iść na Moskwę, 2009

Agnieszka Rayzacher: How did the media react to your work?

O. G.: Konstfack is the most well known art academy in Sweden, and the best art academy. Everybody loved it until Anna Odell and Nug came along. People in general demanded that the university should stop projects like that. There were questions about why students weren't receiving enough control. But as for my work, people thought that Konstfack had taken it too far by banning my work, which worsened even more the already negative image of the academy. I even got letters from people supporting me.

A. R.: But people in general or people from the art world, art critics? Because this is a very important question about who is interested in these scandals - the society in general or just the artists and critics?

O. G.: I'd say rather everyone. Everyone loved me and everyone hated Konstfack. Not even people from the art world, even though they liked me.

A. R.: And how did you feel? Were you happy about the reaction of the academy?

O.G.: I expected a reaction, I provoked it myself, but I was quite surprised that the scandal made it outside the school, I didn't think things would go that far. I just wanted to attract the attention of the professors. But when it all grew huge, I wasn't disappointed at all, quite the opposite.

Teodor Ajder: So you got the grant thanks to a scandal?

O.G.: No, it wasn't that way. I was supposed to get the grant because I was the best, but I was afraid that people would forget about that. I thought that a scandal would effectively remind them of me. That was in my head. So I didn't get a grant because of the scandal.

T.A.: And how did you know you were the best?

O.G.: I'm young. I've just graduated from school. I'm no one. But you can't go around thinking that you are no one. You have to think you're the best. I may not have been the best student but I thought so.

T.A.: Have others tried that as well, also at other academies?

O.G.: It was possible only there and at that time. I've heard someone tried to do that somewhere else, but it didn't work. I mean because it was not at Konstfack.

T.A.: Has everyone everywhere liked your work?

Oscar: In Moscow they didn't like it at all. The thing is that the marching songs are all about killing Russian soldiers and their children, raping their wives and burning down their villages.

Teodor:

A.R.: I'm very interested in the presence and the role of the media in art scandals. In Poland, it started at the beginning of the 90s with the reaction to Katarzyna Kozyra's work Animal Pyramid. At that time the first independent media started to emerge in Poland and even though we didn't have tabloids, the first scandals were very powerful. What is the role of the media in this sphere in Sweden?

M.S.: I think that the role of the media is of course very important, but it's not only about scandals. Art works go outside the art world and are discussed in the free media. When there is controversy, it always unfolds in the same way: they take two people educated in the field, two people who write a blog, two people who are against everything and two who support everything. Each of them is given 15 seconds to speak. It's too little to actually say something worthy. So the media is interested in the debate, but the art world is ready to do everything to preserve the privilege of deciding which artists are good and which are not, and who should be promoted. So the interest of the media can bring nationwide attention, but also reluctance on the part of the art world.

Anna Odell, Rekonstrukcja, 2009, wideo, widok z wystawy w lokalu_30

Kamila Wielebska: Scandals are part of the work of the media. But I think a more important question is if we are really interested in producing scandals for the needs of the media. We've been invited here to discuss provocation and scandal in art. But are these really important concepts for us? When I was preparing for this meeting, I found on the Internet about the events called Pepp-March For Art, yearly marches initiated in 2009 in reaction to the Konstfack scandals and "the debate that criminalises artistic creativity"1. The notions of artistic activity and creativity were evoked. And I thought that maybe these notions are more important for us when we're talking about the social role art. When I was reading about those marches, I recalled Polish Orange Alternative, grassroots movement active in Poland in the 80s. Those people organised funny actions in the streets, in the public space, attracting passers-by, who were eager to join in. I think that the activists of the Orange Alternative didn't think about themselves as artists, but they wanted to cause social changes, inspire activity in the enslaved and passive society. It was against the totalitarian system which surrounded them. Their activities may have been inspired by the Provo movement in the Netherlands. What they did was the very artistic activity and creativity, able to trigger social and even political change. And people joined them, they felt it was something important, it was something they needed. It was joyful resistance against the totalitarian regime. The essence of those actions was to show, demonstrate how the regime worked. The totalitarian system operated to target the activity of some people against the activity of other people, so that they develop a conflict. Obviously, any collaboration disappeared between those people, divided into groups. When I saw Anna Odell's work and Nug's work, I thought that what they did was to destroy the work of other people [Anna Odell walked nervously and appeared highly agitated on a bridge, taking off her clothes and producing the impression that she wanted to jump from the bridge - she was forced to leave the place and taken away by a special rescue team. In turn, Nug entered an underground station equipped with spray paint, which he used to paint all over the underground car, and broke one of its windows.] Personally, I find it difficult to see artistic activity and creativity in their actions. You've said, Martin, that the rescue team who took away Anna Odell demanded an apology. And the refund of the incurred costs. I think they were right. It was their job, which they did, and at that time someone else might have really needed their help. In a way, they were also mocked. So for me, the demand to refund the costs of the action has more of a symbolic than material meaning. It's really about their work and involvement.

M.S.: But art is not obliged to indicate norms of morality. On the contrary, we can deal with a really good art work that questions these norms.

K.W.: Yesterday, I saw an interview with Gayatri Spivak. She was asked if she believed that art can produce social changes2. And her reply was very short: no. But I think she's wrong, because for example the already mentioned actions by the Orange Alternative contributed to certain changes in Poland, which were important for us at the time. One week ago, I was in Gdańsk at the opening of the exhibition of Gilbert & George. They underline that what matters for them in art is its moral dimension. And they treat morality as an ability to change things - which only artists and philosophers have. It is them who can give a moral dimension to things and events, and make us see them in a different way. This is the most important thing in art.

O.G.: But what is social change? I mean everything we do can amount to social change.

K.W.: But not everything is art. For example, I can read your work in a different way from Anna Odell's and Nug's works. I think that you are showing the mechanism of the system. You put some sentences on the flag which make us realise how anger and hatred is produced by the system, how we're drawn in by those who control us.

Kaja Pawełek: But isn't that the question of the form. Wouldn't there be a difference if Oscar had made a film with Swedish soldiers singing those songs?

K.W.: What's important in this kind of works is whether they've spoiled and disturbed the work of other people. People from outside the art world.

K.P.: This is exactly about this moment when the audience is involved through manipulation, creating a certain social or public situation around the artistic activities. Artists are eager to use in their works ordinary people met on the street, as somewhat of unaware actors, extras. The audience of the activities becomes part of the recorded situation, usually unaware that they're dealing with art. A member of the audience is a normal person who is alarmed by someone's aggressive behaviour on the underground. And the first, totally normal reaction is not to say: "Oh, that's a really good performance!", but to take out your mobile and call the police..

Zuzanna Janin: I wouldn't call the police.

K.W.: If I'd been there, I'd have called the police.

Z.J.: It was a social-cultural situation. Totally provocative and very telling about the protest against the system. I think it's very interesting and I think that calling the police is something very reactionary.

K.W.: It was wasting public money. And someone's work. Someone has to clean that underground station.

Z.J.: What does it mean public money? This is my money.

K.W.: Also mine.

Z.J.: I think one should spend a little bit of money for the sake of social change.

K.P.: I think it's very attractive when you see it at the gallery, but it's totally different when something like this happens on the street and you have to participate. I'm trying to figure out the situation on the underground as a play on the figure of a terrorist, a radical breach of the social pact on non-aggression and normal behaviour, etc. In the real world, it's something that can easily disturb people in a public place. At the gallery, when the context is obvious, it's very nice to watch, with trance music in the background and a glass of wine in the hand.

This is where the question emerges of ethics in what artists do and the problem of limits. Scandal always refers to taboos or critical issues for the society. But with the works we're discussing here, the reason for scandal is totally different than with scandals in Poland. So we can also treat it as an indicator of what really touches the Swedish public. The artists' activities that undermine the valid norms reveal the values that are important for the society. They show how the society works and what its foundations are. As far as I understand, the goal here was to show the mechanisms that create a very institutionalised structure in Sweden. To show that the society got stuck in all those institutionalised forms, which used to provide the basis of the pro-social ideology of the welfare state, but have practically turned into their own opposite, excluding any kind of controversy, debate, freedom.

Elin Magnusson, Wysiadaj, wideo

Z.J.: First of all, I'd like to say that a scandal never unfolds on the part of the artist. On the part of the artist there's a different stage of the process: provocation, which is to trigger some changes, draw attention to a problem or question something. On the part of the artist, there's a certain anticipation, what will happen next. And in my opinion, we all lose when a scandal emerges. Especially if the scandal appears in the very sphere art: among curators, institutions. If they regard something as a scandal and call it a scandal - they, and not the media - then it becomes dangerous. Because when the media do it, it's usually in their own interest, e.g. to sell more copies of a newspaper, etc. We have to make it clear. If we don't derive from these provocations any intellectual conclusions - which is the task of the people from the art and culture world - but follow a scandal created by the media. It can easily destroy the artist and exclude them from the art world, just like it was the case with Dorota Nieznalska, who had always been a good artist, but suddenly, after the scandal around her work, she became a bad artist. I think that the very moral issue is what we need to solve. But it can also happen that a work will be lost and you can only hope that someone open enough would appear who would say despite the scandal: "No, I want to show it" - just like Grażyna Kulczyk did with Nieznalska's work. Kulczyk is independent and has enough money not to be afraid that someone would scratch her car, throw eggs at her window or harass her. Such a person provides a chance to reclaim the work to the context of intellectual interpretation. I wasn't that lucky when I did my work I've Seen my own Death. I was preparing it in cooperation with curators for an exhibition at the Foksal Gallery, but when the media started a bigoted witch-hunt, an alliance between the artist and curators was lacking. The press went mad... I was left all by myself. Much to my surprise, writers on art also turned it into a scandal. It even went that far that some parents wanted my son to be expelled from school. With regard to that experience, I think that an alliance between the critics and artists is necessary; anyway, artists should be informed already at the studies that they should cooperate with curators and the media, and how to deal with a work that can potentially turn into a provocation. They should always have someone to cooperate with, who would help proper realisation, or even become their "spokesperson". Oscar managed very well with it - you can tell he's very intelligent. He figured out the system very well. Of course not every artist is able to do that. When I was doing the action I've Seen my own Death, the curators supported me at the beginning, but when I was accused of a scandal, I had to manage on my own. I was invited to a TV programme; I said I'd agree as long as I wasn't attacked, and the conversation remained content-related, on art, on death - it got a promise but the TV host didn't keep his word. Then I realised it couldn't be like that any longer - I decided to wear a "pregnant costume" to every meeting or debate - (such "pregnancies" were worn by girls in my performance WCIĄŻ). It's important that by simulating pregnancy, I enforced content-related, peaceful discussion. And suddenly it turned out that they it's possible to talk to me in a normal way! Then I changed the "pregnancy" for the camera - I went to a TV studio with a camera and recorded what the hosts were saying, which effectively disciplined them. That's why I think that artists should understand and use different tools, going beyond the safe gallery space. I also learnt this from Harald Szeemann, when I was experiencing his exhibition "Beware of Exiting Your Own Dreams. You May Find Yourself in Someone Else's". In other words, it's about sensitivity to a certain kind of manipulation of the visual in the frame of what's broadly understood as art. It's about affecting our senses and imagination with different means in order to trigger a change in the perception of reality. It's a very important field of artistic activity, which stands a chance of changing stiff social or cultural relations. And as far as the already mentioned ethical issues are concerned, there will always be a problem, because there's an activity which is morally normative, and an activity which can be redundant or improper in the field of art. I'm not saying that the artist is free to do everything, but just that every profession has a different code of conduct. And mixing these discourses makes people lose the point. Even the text on Oscar's flags can be unacceptable from the point of view of normative ethics, or maybe military rules. So what? His work operates in the field of art and it's very good. It shows the absurdity and mechanisms of developing aggression. Ai Wei Wei faces serious troubles in China, he is accused of pornography, among others, while he made exquisite, really beautiful photos of naked people. Most galleries in the world crave for those works, but the Chinese authorities think that they are unacceptable, so they manipulate the sphere of normative ethics. Getting back to my experience: as I've said, when my work made it to renowned collections, it turned out that it's appreciated and worthy. Norms and ethics is a topic for very delicate discussions. When you make provocative art works, you breach the set limits, you shift them more or less, risking the "inappropriate" emotions of some people, while extending the field of vision of reality of others, or defending them against the oppression of the world. In this sense, I can see a real impact of art on the social sphere. The artist always protects someone in the sphere of action in art. Event if they "offend" religious feelings, national flag or well-being of others... It's then that they defend someone who suffers from ideological, political, social or cultural oppression inflicted by the above mentioned factors.

A.R.: Can art have an impact on social change?

Z.J.: I truly believe so. But these are long processes. We often launch activities in one sphere, and then they are shifted to another, with realisation occurring in a totally different field. As far as I understand, that was the case with Anna Odell, whose work is situated, as I think, between the interest of the society in the hidden problems of mental illness and death, and the social annihilation because of a mental illness. Therefore, her work triggered a debate about mental illnesses, from which many people are said to suffer in Sweden, but the topic is avoided in the public sphere.

A.R.: Let's get back to our guests. Martin's presentation has given us a very interesting image of Swedish art and I think we already know what artistic provocation actually is in Sweden, and at what it is really targeted. It seems that it is targeted above all at the state system, the very state, while in Poland the provocation is targeted above all at social taboo, at something that in reality has been swelling within us for centuries.

Zuzanna Derlacz: For me, Oscar's work was targeted more at the very state and the relations between history and the present image of Sweden, at least the image that we've forged. Unlike his colleagues who rather acted against social relations. Why wasn't there a negative reaction on the part of the media or the authorities, as it would certainly be the case in Poland? Does it stem from a different approach to the state and nation in our countries?

O.G.: It would have been exactly the same in my case if it hadn't been for the venue where the project was realised, a very special venue for art scandals. People didn't even see and know the text, but accused it just in case. The reaction of the audience in Kalmar was the same.

noted by: Adrianna Lau, translation into Polish: Łukasz Mojsak