The New Animal Taxonomy: rendering animalsvisible in Sue Coe's slaughterhouse sketches

Sue Coe's illustrated narrative, Dead Meat, is a visual chronicle of the slaughterhouse industry in the United States, Canada, and England and is a journal about the materiality of animal death. Written in a quasi-journalistic format with accompanying drawings and sketches, Coe uncovers the realities of abattoirs, slaughterhouses, and industrial farms where much of our meat, eggs, and dairy products are rendered into consumable form. She recognizes the fractures and destruction in the death of livestock animals and points to how these fractures create space for new ways of thinking about and animals and our relationship to them. By reading against more traditional forms of representation, Coe creates new ways of categorizing livestock animals, rendering them as individuals apart from any taxonomic categorization. In this essay, I argue that a double-meaning of the term rendering takes shape in Dead Meat, one that Nicole Shukin refers to as, "both the mimetic act of making a copy, that is, reproducing or interpreting an object in linguistic, painterly, musical, filmic or other media and the industrial boiling down and recycling of animal remains1." I go on to illustrate how Coe's particular rendering of slaughterhouse animals allows for new taxonomic structures to form within the animal world and its relationship to human beings. This alternative definition of animal taxonomy is unrelated to traditional Linnaean hierarchies and will, in fact, propose a disordered system of classifying the animal in an attempt to understand it incompletely. Finally, this new taxonomy, which I refer to as a folksonomy, allows animals to take shape as individual beings, capable of unique identity, although their lives are condemned to anonymity in slaughterhouses.

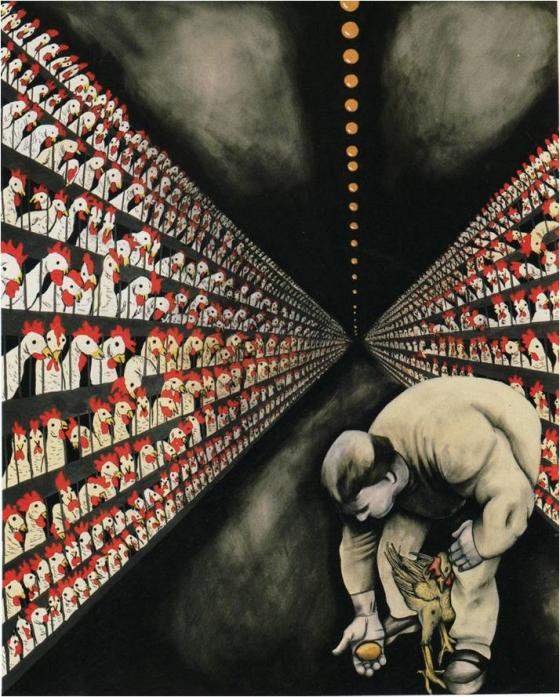

Sue Coe, Egg Machines, Dead Meat, © Sue Coe

Sue Coe emphasizes the importance of taxonomy and visual particularity from the beginning of her life. "There were four books in our house," writes Coe at the outset of Dead Meat, "Aeroplanes of the First World War, Sex in Marriage (with diagrams), The Holy Bible (with paintings of hell), and How to Sew (with diagrams). These books were looked through many, many times.2" Text, in conjunction with images or ‘diagrams' seems to be the fundamental channel through which Coe received most of her information as a child, and this mode of pairing images with text, producing visual taxonomies of information, is what defines Dead Meat.

As I previously mentioned, I take my definition of rendering from Nicole Shukin's book Animal Capital: Rendering Life in Biopolitical Times. In Animal Capital Shukin takes rendering to signify, "both the mimetic act of making a copy, that is, reproducing or interpreting an object...and the industrial boiling down and recycling of animal remains.3 " The double entendre is, "deeply suggestive of the complicity of ‘the arts' and ‘industry.'4 " In death, livestock are rendered into parts, whether it be through the slaughterhouse, incinerator, or natural processes, the animal goes from being a visible whole, to a fractured set of parts: cuts of beef, racks of lamb, or ground hamburger meat. Coe's project in Dead Meat is both an instructive tool to show how animals are broken down, but by the same token her images preserve the animals and render their individuality.

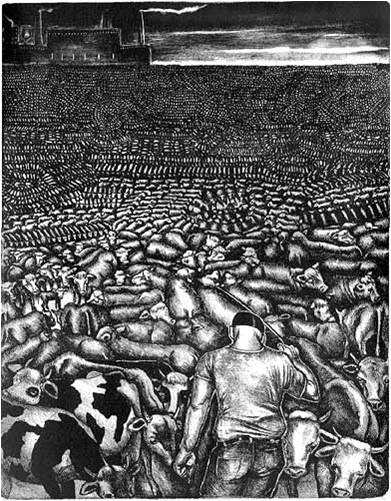

Sue Coe, Feedlot, Dead Meat, © Sue Coe

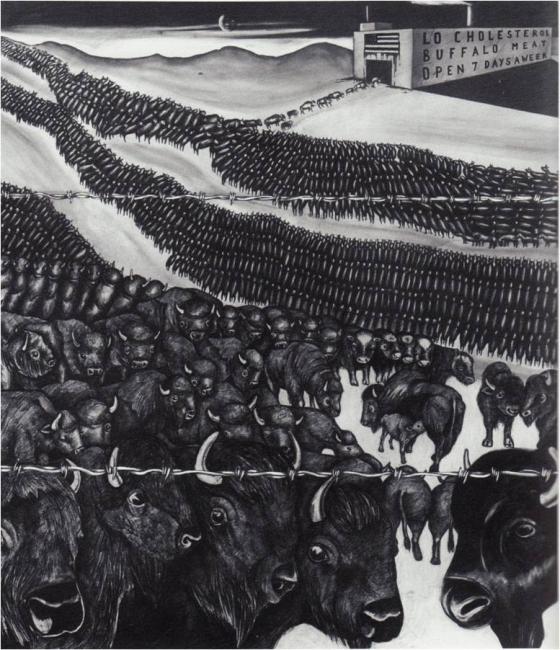

Sue Coe, Lo Cholesterol Buffalo, Dead Meat, © Sue Coe

Many of the paintings and sketches in Dead Meat oscillate between scenes of the immensity of animals in slaughterhouses, to telescopic views of an individual animal life and suffering. In Feedlot and Lo Cholesterol Buffalo Coe presents a seemingly endless supply of cows and buffalo at a New Mexico dairy farm and a Missouri stockyard. Each animal is nearly identical to the next, organized into neat configurations, and the sheer amount of animals present leads the viewer to think that one life is not distinguishable from the next. In two paintings paired together, Egg Machines and Debeaking, Coe shows an isle of egg-laying chickens with a vanishing point beyond our sightline and on the opposing page a close-up of a debeaked chicken with a bloody stump where a beak once was. These types of depictions play with the notion of how animals are rendered in plentitude. Anonymous and infinite, livestock are divorced from their identity as sentient, conscious, and unique life forms. Instead, rendering them en masse makes it easier to dispose of them and break them down into useable parts. It is through their plentitude that we are able to discard their individuality. This notion also plays in directly with traditional taxonomic structure. In Linnaean taxonomies, animals of the same species are not considered unique. They share the same physical features, attributes, and behavioral characteristics, therefore allowing individual animals of the same species to be indistinguishable from one another.

However, as we see in Debeaking, Coe negates this type of categorization. We see a telescopic view of a de-beaked chicken in the lower part of the drawing. One that is unique from the others in the basket. Our individual chicken has her own identity, suffers, and looks undignified without her beak. She is not part of a structure or categorization; instead she is her own being, imbibed with suffering. Much of the reason Debeaking has such an impact is because of the particularity of the chicken's face. It's as if Coe has painted a portrait of this animal before her death.

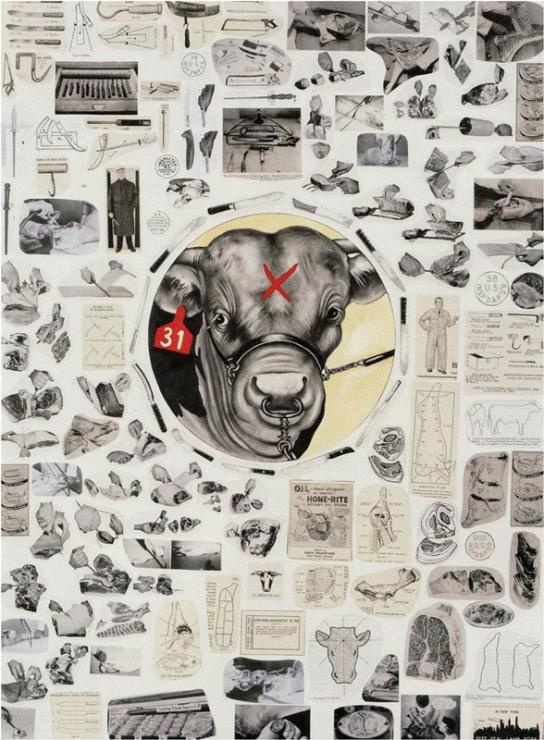

Sue Coe, X Marks the Spot, Dead Meat, © Sue Coe

A similar rendering takes place in a portrait collage, X Marks the Spot of a particular cow, #31, who is surrounded by taxonomic drawings of cuts of beef and slaughtering knives. Our attention is drawn to the cow's face but the cuts of meat and diagrams serve as a distraction. However, it is in the cow's face that we recognize and identify life. In Cary Wolfe's essay, "From Dead Meat to Glow in the Dark Bunnies," he speaks of the face as Emmanuel Levinas's "site of an unanswerable obligation...in an infinite responsibility to the other.5 " Thus, if we look at X Marks the Spot through the notion of responsibility, we see how the face asks us to disregard the anonymous categorization of taxonomy and address the individual cow that stares at us from inside the collage of its parts. Taken in this light, Coe's portrait of cow #31 is both a comment on the obsolescence of taxonomy-as the beef cuts are entirely devoid of identity-and a vision of the double entendre of rendering, the breaking down of the animal into parts and the depiction of the animal as a whole being.

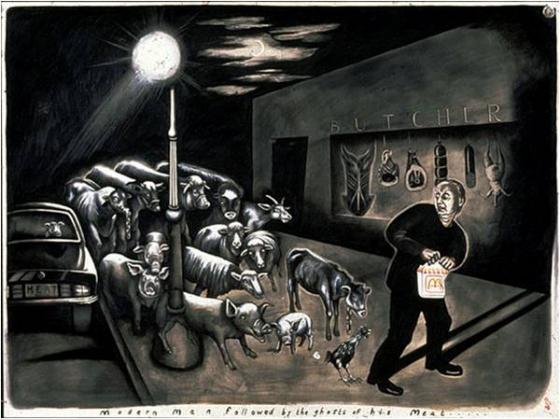

Sue Coe, Modern Man Followed by the Ghosts of his Meat, Dead Meat, © Sue Coe

Coe tests the notion of our relationship and responsibility to animals in the paintings Modern Man Followed by the Ghosts of his Meat and Sausage Counter. In these depictions, Coe asks us to reckon with our intimate relationship to consumable animals. Alice Kuzniar, who writes about our relationship with dogs, called dogs an "extimate" species to humans, "extimacy being that which is exterior to one yet intimately proximate.6 " Livestock animals such as cows, pigs, sheep and chickens suffer under the term extimacy. Unlike dogs, their intimacy with humans comes in the consumption and absorption of their bodies into our own. Their bodies essentially become more valuable dead than alive and our intimate understanding and manipulation of their bodies' fuels an industry devoted to the regulation, death, and breakdown of their body parts. Humans are extimate to livestock in that we rarely have daily contact with living, breathing, livestock animals, yet we are intimately acquainted with their body parts as incorporated into our meals, our clothing, and some of the products we buy and consume. Coe problematizes this extimate relationship in Modern Man Followed by the Ghosts of his Meat by showing what our actual experience would be if our meat had a face and our understanding of animals had more to do with their life than their death. Furthermore, this painting, along with Sausage Counter shows how distancing ourselves from meat, packaging it in anonymous and strange forms, allows us to maintain power and control over animals. I link this directly to taxonomy, which essentially creates power relationships between sentient beings.

Steven Wise aptly says that taxonomies from Aristotle to Linneas and Darwin are created to "busily fashion the world into a ladder upon which [humans] occupy the top rung.7" Genus, family, and species are organized according to traits and various other factors, but essentially, humans rise to the top as the dominant species. However, our rankings are based on a structure built out of human imagination, which disallows other beings any access to the top.

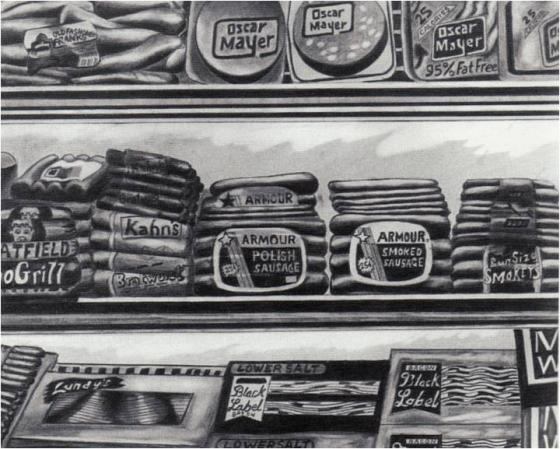

Sue Coe, Sausage Counter, Dead Meat, © Sue Coe

For a moment, let us look back at the image of the Sausage Counter. These seemingly formless objects, in neat and tidy packages, are estranged from the terror and cruelty of the killing floors in slaughterhouses. They are completely devoid of identity, particularly in relation to the pigs that actually gave their lives to create the sausages, bacon, and cold cuts pictured here. Sausage Counter speaks directly to the lack of identity animals have in death. They are disallowed specificity and become simply ‘meat' to those that see a package in a supermarket. In The Electric Animal, Akira Lippit speaks of the "convergence between eating and seeing," and asserts that, "animals can only appear as matter-meat-because they possess no discernable identity.8" It seems to be Sue Coe's goal to refute this statement. She takes great pains to make visible the animal's identity, give them particularity, and show the destruction that occurs in the animal's journey from birth to the dinner table.

In thinking about Coe's purpose with a book like Dead Meat, I came to the realization that Coe had created her own type of "botched taxonomy" of animal nature. As a play on words from Steve Baker's theory of "botched taxidermy," in which he says that "botched taxidermy" is characterized by, "those instances of recent art practice where things...appear to have gone wrong with the animal, as it were, but where it still holds together.9" In Coe's work, we see how things go terribly wrong with the animal at the hands of the humans held responsible for them. In a stockyard in Pennsylvania, Coe describes, "one female goat in particular. Her stomach has been ripped out, probably in transport. It has not come out completely, but is hanging by the fur and skin...the goat won't be put to death swiftly, because she is still standing.10" Another example is the painting of the de-beaked chickens staring blankly at the viewer after having their beaks clipped off. In both of these instances the animals are "botched" in some way, but they still hold together in the form of an animal. In many ways, this is another moment where Coe implicates the double meaning of rendering. The animals' bodies are literally breaking down at the same time that Coe is preserving their images through her brush and pencil. Finally, these animals refute traditional notions of taxonomy because they actually lack the inherent characteristics given to other members of their species-a beak would be a fundamental physical attribute of a chicken, and the four-chambered stomach of the goat would be crucial to her identification as a ruminant.

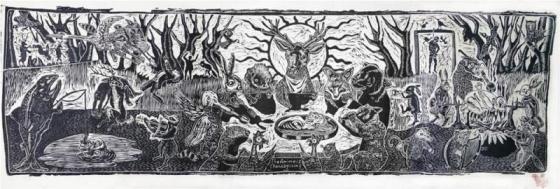

However, Baker's definition of botched taxidermy and my appropriation of the term do not quite convey the empowering aspects that Coe grants to the animal in works like Man Followed by the Ghosts of his Meat or her woodcut, The Animal's Thanksgiving. Instead, I look to the field of modern library taxonomy to provide an apt definition of Coe's project. I would like to propose new forms of animal taxonomies that allow for partial, if not incoherent, knowledge of animals. Unlike traditional taxonomies, which break down animals into categories of species, disciplines, or geographic areas, this new form of taxonomy might best be described as animal folksonomy. Folksonomy is a hybrid of the terms ‘folk' and ‘taxonomy' and emerges from the information science and social tagging realm as a way to organize information communally. In Daniel Pink's December 11, 2005 New York Times article he calls folksonomy, "grassroots categorization," that is, "idiosyncratic rather than systematic.11" Folksonomies serve as unique identifiers that are invested with meaning from the ground-up. They are the grassroots organizing tool of the taxonomy world and their value only increases as more individuals come to mutual understandings about the role and place that a particular ‘tag' plays in identifying an object, act or individual. Folksonomies develop without a hierarchical imposed structure, and are therefore seemingly less ‘organized,' however, this lack of imposed organization allows for creative ways of naming, classifying, and understanding things.

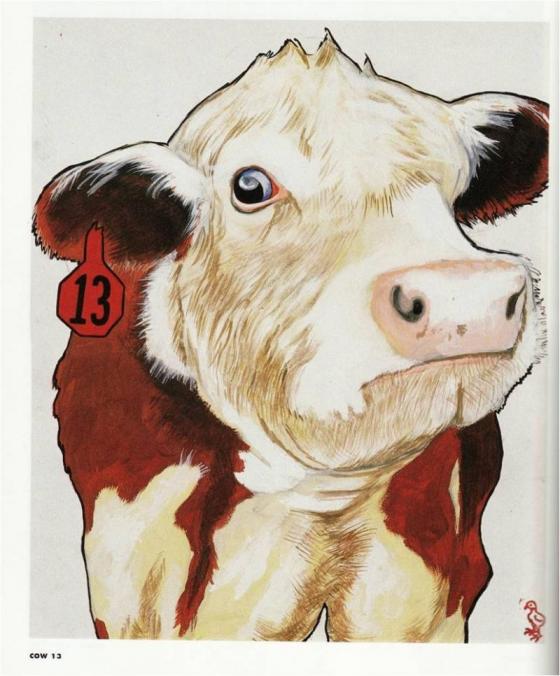

Sue Coe, Cow #13, Dead Meat, © Sue Coe

This idiosyncratic approach allows for a remaking of the animal on its own terms, promotes incoherence, encourages fractures, and ultimately emphasizes particularity and uniqueness over the idea of conformity and similitude. Folksonomies break down meanings and utilize new visual and textual vocabularies. "[It] is not so much categorizing," writes information architect Thomas Vander Wal, "as providing a means to connect items to provide their meaning in their own understanding.12" Folksonomy's approach to taxonomy is more ethical and participatory and allows the animal to be rendered visible through each instance of the animal's being, as opposed to a representation or metaphor that attempts to speak to the broader definition of animal.

In X Marks the Spot, we see how traditional cow taxonomies break down the cow into ambiguous parts but do not provide space to actually see the animal. By placing the face of the cow in the center of the collage, and connecting that particular cow with the accompanying taxonomy, Coe asserts a new taxonomic or folksonomic order into the understanding of the cow-one that allows for the idiosyncratic, individual, and uncategorical identity of this particular cow to take precedence over its anonymous parts.

In Man Followed by the Ghosts of his Meat, Coe imagines a disordered world, lacking the traditional structures of power provided by taxonomy. A pig watches the fearful human idly from a car, while a horned goat bears his teeth like a predator, and a chicken at the man's feet calls out repremand. Meanwhile, the man has the same petrified look that Cow #13 has before she meets her end at the slaughterhouse. The animals in these paintings have power. They stare at the viewer with strong and unique faces and the anonymous ground beef hamburger and beef cuts lose their appeal.

Sue Coe, The Animal’s Thanksgiving, Graphic Witness, © Sue Coe

A similarly powerful scenario takes place in Coe's woodcut, The Animal's Thanksgiving, which depicts a series of animals reveling in the hunting, killing, and cooking of humans. Taken together, these images act as a refusal to participate in the traditional coding and categorization of life on earth; instead they supply an alternative order or disorder to our understanding of the relationship between humans and animals entirely. The ladders upon which traditional notions of taxonomy stand are completely disregarded, and have been replaced by the animal's understanding (or Sue Coe's hope for them) of their place in the order of things.

To what ends does this type of visual cataloging serve? Coe has little commentary on attempts made by activists or politicians to reform the animal slaughter industry. Instead, Coe renders the animal visible in order to serve as a witness to the fractures, eliminate the smooth exteriors of the industry, and interiorize her viewers into the horrors of animal slaughter. "My quest," writes Coe, "to be a witness to collusion...requires witnesses.13 " Thus, the viewer is implicated into the structure of rendering the animal-both breaking it down and creating an image of it. Coe's act of witnessing becomes our act of witnessing and draws us closer to the being of animality. We become invested with the power to help make meaning for these slaughtered animals and provide new ways of talking about and rendering them.

In his introduction to Dead Meat, Tom Regan comments that,

Like us, these animals embody the mystery and wonder of consciousness. Like us, they are not only in the world, they are aware of it. Like us, they are the psychological centers of a life that is uniquely their own. In these fundamental respects humans stand on all fours, so to speak, with the hogs and cows, chickens and turkeys. What these animals are due from us, how we morally ought to treat them, are questions whose answer begins with the recognition of our psychological kinship with them.14

In Regan's terms, Coe explodes the traditionally oppressive taxonomies that separate animal from human and levels the scales to render both human and animal on the same plane. Thus, not only do we become kin with animals, but they also become our folk. Here, the term folksonomy implies a camaraderie and shared understanding of one another. As we allow ourselves to "stand on all fours" with animals we are able to recognize our similarities in suffering, in dying, and in wanting to be treated with respect. Coe's animal, made visible through this new knowledge of the animal as animal allows space for a new ethical taxonomic understanding of what it means to be an animal or a human in and aware of the world.

In a sense, we create our own folksonomies. As we share new ideas and bring into focus alternative ways of understanding our relationship to animals, we create new semantic spaces and ways of ordering the ladders upon which we stand. These upsets and ruptures in the established scientific hierarchies seem disorganized at first, but they allow for a more democratic and participatory interaction to take place between human and animal. Artists such as Sue Coe strive for this disordered and ruptured representation, and we should only be so lucky that a new order would come about.

- 1. Nicole Shukin, Animal Capital: Rendering Life in Biopolitical Times (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009), 20.

- 2. Coe, Dead Meat, 39.

- 3. Nicole Shukin, Animal Capital: Rendering Life in Biopolitical Times (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009), 20.

- 4. Shukin, Animal Capital, 20.

- 5. Cary Wolfe, "From Dead Meat to Glow in the Dark Bunnies: the animal question in contemporary art," in What is Posthumanism? (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010), 147.

- 6. Alice Kuzniar, Melancholia's Dog: reflections on our animal kinship (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006), 8.

- 7. Steven Wise, Rattling the Cage: Toward Legal Rights for Animals (New York: Perseus Books 2000), 134.

- 8. Lippit, Electric Animal, 182.

- 9. Steve Baker, The Postmodern Animal (London: Reaktion Books, 2000), 56.

- 10. Coe, Dead Meat, 72.

- 11. Daniel Pink, "Folksonomy," The New York Times, December 11, 2005.

- 12. Thomas Vander Wal, Folksonomy, February 7, 2007, http://vanderwal.net/folksonomy.html (accessed April 22, 2010).

- 13. Coe, Dead Meat, 72.

- 14. Coe, Dead Meat, 2.