A change in a society struck by crisis: an interview with Francis Alÿs.

[PL] ZOFIA MARIA CIELĄTKOWSKA: Let's start with the main movie of the exhibition "REEL-UNREEL" (2011), which I think might be interpreted on different levels. The first level could be described as political, and is connected with the fact that Talibans on the 1st of September 2001 confiscated and damaged reels from the Afghan Film Archive. On the other level - as the celluloid of the movie very literally absorbs the dust of the city streets - we can find a story about the movie itself. This mechanism of absorbing, reminds me of your previous work "Zapatos Magneticos" (1994) - in which you walk with magnetic shoes. There is also another level placed beyond visuality - I'm thinking here about the real project, the experience of physically being there.

FRANCIS ALŸS: My first intention - and this happened before I went to Afghanistan - was to explore and analyze my relation to film. I have been using video for about 20 years. I think that the transition from analog to digital provoked massive changes. In the post-internet era, the way of handling "moving images" is so different than just a few years ago. We are informed about conflicts happening in faraway places by movies made with mobile phones. Very basic cameras become the main register of historic events. When I was invited to this project, I was very skeptical about my potential comments about Afghanistan, knowing so little about the place.

From a European or "other" perspective, Afghanistan is "somewhere there". You live in Mexico City.

There is little relation whatsoever between Latin America and that particular part of the Middle East. Before being invited to produce a project in Afghanistan, I had a lot of doubts about the ways in which to register performances. The first phase of the project was a very personal investigation. I was very much thinking about my own practice, my relation to image in general. I used that as an entry point. Afghanistan is such a vast and completely unknown territory to me, that if I hadn't had any parameters, I would have easily gotten lost. You encounter so many foreign codes. It is easy to take a wrong path. I decided to stick to my own narrative as a way of infiltrating and eventually later interfering with the place. There were specific reasons why Afghanistan was a good place to work on the topic of image. Partly because of the complex approach of the Muslim culture to the image in general, partly because of the tragic episode of the Taliban burning the Afghan Film Archive, and also partly because of the distorted media image we receive of Afghanistan. Once these questions were in place within the context, it became a sort of a dialog. There were two phases of the project; the first one, as I said, was personal. The second phase was about: how will the location react and meet my original intention. Once you have consolidated your position, it is easier to absorb information and build a narrative thread. I'm using the journey of an endlessly unrolling reel to find a way of portraying Kabul. This mechanism of the game, where two boys are chasing one with another, allowed me to show Kabul from a different perspective. It is not the Kabul presented in media, but from the point of view of everyday life. The boys were showing us their city - the Kabul they know; we had to follow them. They took the lead in terms of writing the script. It happened spontaneously, they took over the narrative and told their story. The development of the film was relatively out of my control and I very much appreciated that. I set the situation and I let it develop by itself, by inertia. From my scenario they made their own story, and I love that. I like my situation of following them rather than directing them.

Francis Alys, "REEL-UNREEL (Afghan Projects, 2010 - 2014)",

video documentation of an action, film still, Kabul, Afghanistan, 2011.

In collaboration with Julien Devaux and Ajmal Maiwandi.

Courtesy of an artist and David Zwirner Gallery, New York/London

It is also visible in the way of filming that the camera takes the children's perspective. The shots are taken from a really low position. Even here in the exhibition, in the place where people can watch the movie, there are mattresses on the floor - the viewer is somehow asked to take a horizontal position. Another thing is - when you look at these boys - they are just having real fun.

Yes. They took it like a game and treated it as an adventure. If you work with kids, it has to be fun. They will quickly lose interest if it's boring. So you have to follow their impulses and rules as well.

You have mentioned this personal aspect of your work and I'm thinking of your relation to the people taking part in your projects. Your works usually require really good organization in terms of production or logistics. I'm thinking of works such as "The Bridge" (Cuba, Florida, 2006) or "When Faith Moves Mountains" (Lima, Peru, 2002) - but it is just one part of it. I suppose you have to talk, spend some time with people to convince them to take part in your work. There is a personal level which we are not able to see in the documentary videos.

In the film, what you see is the end result of weeks or months of discussions, sharing meals, sharing time, visiting and watching, learning, etc. There has been a long process already ongoing by the time we reach the filming stage - and that is a part that doesn't show very much. I'm trying to give the viewer some of that process with the notes, studies, emails, etc., that trace the life of the project. If you have to put all of the experience of the project in a timeline, the filming barely represents 5 % of the project's actual real life. The remaining 95 % is visiting, discussing, learning, reading a lot, and trying to understand the situation; mostly listening to the people.

This contrast is easy to imagine in "Watercolor" (2010), a video in which you take a bucket of water from the Black Sea and put it into the Red Sea. The video is not even two minutes long, but in reality, it had to take some time. The same, I suppose, was with "When Faith Moves Mountains" - the Lima project.

Yes. Especially in the case of Lima it was also quite a long process. We gave talks at universities, youth clubs, etc., to convince young people to participate. It was probably the most evident case where the preliminary production created a platform for discussion. Is it possible to make a change in a society struck by an economic, political, and military crisis? The question behind the project was, if it was possible to get out of this marasm, move to a different stage. The discussions, which we had with the students invited to the project, were about that. When I think about the Lima project, I think mostly of that moment, that space of discussion preliminary to the event. The act of symbolically moving the dune lasted only a few hours. It was just evidence of the whole process that preceded.

Francis Alys, "REEL-UNREEL (Afghan Projects, 2010 – 2014)",

video documentation of an action, film still, Kabul, Afghanistan, 2011.

In collaboration with Julien Devaux and Ajmal Maiwandi.

Courtesy of an artist and David Zwirner Gallery, New York/London

The film, picture, is just a part of the greater whole. That is why I think your works have a paradoxical structure - you use picture and constantly go beyond it. Just as you said, the most important is not given in the film. In case of difficult issues like Afghanistan, there is always a risk that the viewer will not see this gap. It is somewhere there, not here. I think Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev described that problem well quoting Duchamps: "D'ailleurs, c'est toujours les autres qui meurent". If you use picture against picture it can be interpreted as a picture anyway. Do you see this risk in your projects?

It is a risky business. You try to emphasize a critical position, but it is easy to fall into the game of what you were trying to criticize. It is a risk you need to assume. It's not for me to decide whether I managed or succeeded, and it takes quite some time to sense what the public's reaction really is, or how they read the work. There is no stable methodology. You can easily lose yourself in the fantasy of your project, lose connection with reality.

With this exhibition, we start with two videos related to the form of painting ("The Green Line", 2004) and sculpture ("Sometimes Making Something Leads To Nothing", 1997). In the first one, you walk with an open can of paint, marking a borderline; in the second one, you push a huge cube of ice through the streets of Mexico City. I think there are more of your works that could be associated with this kind of "painting" or "sculpture" thinking. The experiment with the line is repeated in few other works like "Painting" (2008) or "The Leak" (2003). Then there are more sculpture projects like "Bridge" (2006), "Barrenderos" (2004) or the already mentioned, "When Faith Moves Mountains" (2002). How do you look at it?

I think more than sculpture, it is a matter of being moved or displaced. Sculpture is something I'm really interested in, but that I have not really been able to produce. For many years, I tried to approach the sculpture field in oblique ways. Many of my paintings are about sculpture, even if though they are images. Actions like the one with the block of ice ["Sometimes Making Something Leads To Nothing", 1997] dealt partly with sculpture. I was trying to open up my relation with the sculpture medium; it is something that interests me a lot, the sole presence of matter managing to provoke an emotion. Yet, for as attractive as it is, I have never really managed to do anything with it. The few sculptures I did were more like toys than sculptures. I did some magnetic dogs and cameras that looked like guns. They were always pretending to be a sculpture, but actually they were just toys. Some day - maybe.

Francis Alys, "REEL-UNREEL (Afghan Projects, 2010 – 2014)",

video documentation of an action, film still, Kabul, Afghanistan, 2011.

In collaboration with Julien Devaux and Ajmal Maiwandi.

Courtesy of an artist and David Zwirner Gallery, New York/London

Your position as an artist is also a really interesting issue. You even suggest it from time to time in the titles. What I'm thinking about, is that you always try to put yourself in a position "between" something. Like between doing and not doing, meaning and not meaning, political and not political, and so on.

I think I know what you are getting at.

This way of suspense is, I think, quite conscious.

I work in contexts where the political ingredient is present, but it is only one among others. I'm not militant. I'm not trying to set a political agenda and so on. But I do take into account the political ingredient as much as the social one, economic one, religious one, etc. For some reason in the last couple of years, this exact ingredient is particularly strong. The poetical ingredient helps me balance it, finding some middle point.

Yes. That's what I'm thinking about.

It's a fragile dance. You can easily fall into a sole poetic reading, which cancels the political ingredient. Then again on the other side, you can fall into the other extreme and it becomes militant art. It is always a challenge to find that balance. Sometimes it is impossible to stay on this thin line.

Francis Alys, Untitled, study for the "REEL-UNREEL (Afghan Projects, 2010 – 2014)",

pen and pencil on paper, 2011-2012, courtesy of an artist

This way of thinking is also present in the video series "The Children Games". Some of the games are quite known and are - let's say - neutral. But there is also a violence immersed in a kind of innocence, lack of reflection or lack of empathy. Here in the exhibition, we can see a video with children in a parallel line with British and Taliban soldiers putting together the guns. That is quite a powerful parallel.

I'm glad that you say that. I place the soldiers next to the children's games because I look at them like adults playing children's games. They are showing off with the riffles, children are doing the same with the plastic guns.

There is some kind of innocence in it, but it is more like lack of reflection, which reminds me of Hannah Arendt thinking about evil.

When I work on projects I don't want to be intuitive, neither do I want to over analyze why I choose this act rather than that one. There is this part of not wanting to know too clearly the reasons. When you understand too much, you can lose contact. You're bored before you even start. I like to keep that slight unknown in the making of the works. When I edit the material it is somehow similar. There is a kind of ritual - children's world in a way.

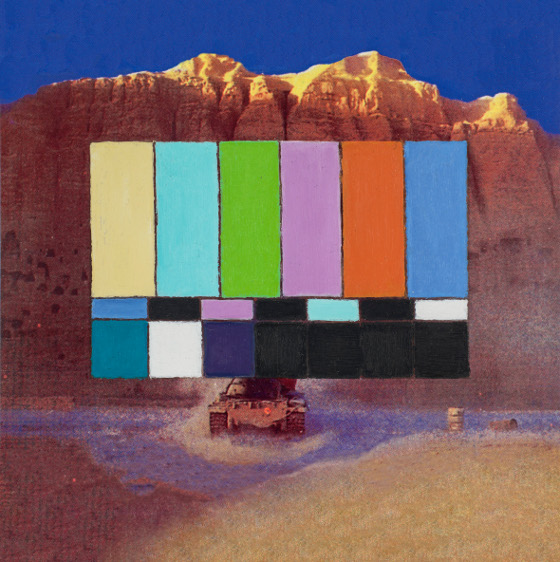

Francis Alys, Untitled, study for the "REEL-UNREEL (Afghan Projects, 2010 – 2014)",

oil on print, 2012, courtesy of an artist

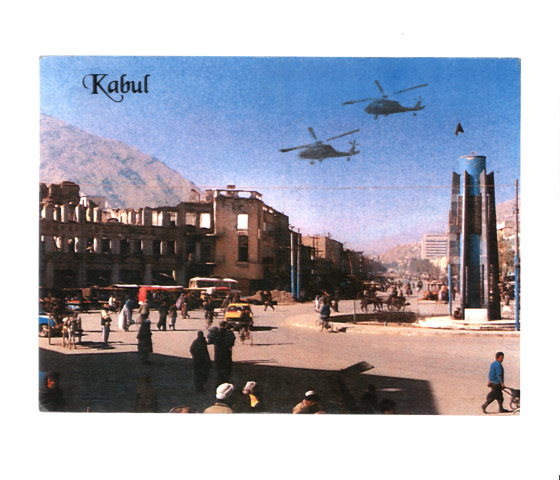

There is another parallel line between the postcards presented in the showcases and small pictures hanging on the wall. The first impression is that they are presenting a nice landscape, some view of the city etc., but when you look at them closer you will see some signs of the war.

In a way, but I'm not trying to portray violence.

No, of course it is not direct.

All I'm trying to suggest is the possibility of violence. Sometimes when I look back at those images, photos, small paintings and so on, I feel it is more a stage of siege than a stage of conflict, especially for the kids who live in that reality. They have grown up in that situation. There has been war in Afghanistan for over 40 years now, so it has become a "normal" environment for them. I imagine war becomes this noise in the background, where life continues. It is the way you perceive it when you are there. There might be an attack in one part of the town, while life goes on in the other.

Francis Alӱs, "REEL-UNREEL (Afghan Projects, 2010-2014)", curator: Ewa Gorządek, CCA Ujazdowski Castle, Warsaw, 10.10.2014 - 11.01.2015

Francis Alys, Untitled, study for the "REEL-UNREEL (Afghan Projects, 2010 – 2014)",

Oil painting on a postcard, 2011-2012, courtesy of an artist