Stories of a 'Disgusting Girl': Cyberfeminist and Trans/National, Techno-Laughter in Mare Tralla's Art

Stories of a 'Disgusting Girl': Cyberfeminist and Trans/National, Techno-Laughter in Mare Tralla's Art1

An account of Mare Tralla's art can be started with a following statement: Mare is not an Estonian artist. Such a claim demands explanation, especially since she is typically included in the corpus of Estonian artists; moreover, her art has for several years been imbued with issues of national identity. The first clarification might be as follows: Mare Tralla is an artist who was born as an Estonian in Estonia and became an artist there; thus, the issues tackled in her art are necessarily based on the experiences that shaped the identity of a young girl who grew up, was educated and chose to become an artist in Estonia during the 1970-80s. But wasn't this Soviet Estonia? Does this make Mare a Soviet Estonian artist (as with those of us who carry the signs and memories of that particular identity)? Subsequent discussion would lead us inevitably to the problem of the formation of a so-called composite identity of Soviet Estonian-ness - a particular configuration of the nation policy of the Soviet era.

The second clarification should draw our attention to the fact that during the newly independent Estonia of the 1990s, Mare became one of the leading artists of the younger generation, having launched an offensive to 'take over' not just the art scene but the media world as well. In this process her art, writings, curatorial practices and public appearances, soon to be known as the interventions of a 'Disgusting girl' - a particular media image created through the interaction of the artist and journalists writing about her - left their mark on both scenes. In the mid-1990s she was one amongst a few courageous women (and men) who understood that for the more harmonious and just development of Estonian society, a 'small feminist revolution' was direly needed. Mare conceived of this 'revolution' in a personal format within the field of contemporary media art. Does this mean that she could be considered as an artist somehow representing the early years of post-Soviet Estonia? However, since her works do not represent the dominant ideology or collective mentality of this period, are we justified in thinking of her in such a way? After all, she preferred to adopt a 'futurist' (forward-looking) and international (outward-looking) position instead of the 'passeist' mentality of the early 1990s, which idealised the 'golden age' of the first independent republic of the 1930s along with its patriarchal values. Do the words used here - 'futurist', 'internationalist' - force us to think of a typically avant-garde artistic position?

The third clarification should state that Mare has been a permanent resident of London since 1996, and that this has not prevented her from working, exhibiting and organising international events of media art in Estonia. However, one ought not forget that during the last ten years she mostly exhibited outside of her original home country. She seems to belong amongst the growing number of nomadic producers of culture, whose names can be found on various lists accompanied by designations of their two home-countries - in Mare's case EST/UK. Doesn't this mean that Mare is first and foremost an international artist? Still, one can never escape thinking of Estonia whilst engaging with her art works.

Socio-critical media art

Mare Tralla became known on the Estonian art scene during the mid-1990s predominantly through her performances and video art, as well as for an innovative TV-series Yes-No about contemporary art, co-created with two of her colleagues, Mari Sobolev and Marko Laimre. From the beginning her works have been associated with such key words as 'autobiographical approach' and 'gendered' or 'feminist critique'. Still, her earliest works such as the expressionist paintings, which remain relatively unknown to the general audience, her almost forgotten performance Destruction of the Illusion(s) (1993), and her video installation Relationship (1994) belong amongst examples of a less critical and more poetic use of artistic language. In 1995 Mare was one amongst the three curators of the first Estonian feminist art exhibition Est.Fem and her own video installation So We Gave Birth to Estonian Feminism was one of the central pieces of the display. Since then, one can trace a programmatically developed trajectory which defines the characteristics of her artistic identity and position.

So we Gave Birth to Estonian Feminism, 1995, video installation

In 1996 I wrote that the place where Mare's life happens is in her art; indeed the works produced during the most extensive period of her participation in the local art scene, i.e. during the final few years before she left Estonia, can easily be characterised in this manner. However, her subsequent works show more clearly the influence of her engagement with various theoretical and technological discourses that characterise the development of contemporary media art. She successfully used the possibility of a spatial and mental distance from her roots, family, and Estonian life, as well as her active involvement in the international media art scene, in creating a trade-mark for her art. She identifies herself with a theoretical and critical subject position drawing heavily on the language of media art and cyberfeminist strategies, and makes use of her personal experiences as a historically, culturally and spatially situated gendered subject. These experiences belong naturally within the constraints of a larger and shared collective identity, e.g. national identity, which although often attacked by the artist she can never leave behind. Her work suggests that we all have our place of origin and that our memories are always mixed with a certain amount of the sense of loss. Thus, Mare's art balances gracefully between social criticism and semi-ironic nostalgia.

Cyber/feminism

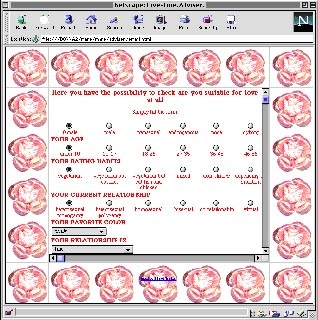

It is generally agreed that Mare is the best-known Estonian artist to pose feminist questions in new media art. For instance, her first home page my very first web-page it does not have a name2 and net project Love-line 3 attempted to articulate specifically feminine experiences both in terms of women's (psychic) reality and their difference from the dominant patriarchal culture and mode of knowledge.

Loveline, net project

These early pieces of net art are significant because here, for the first time, one can recognise the idiosyncratic use of artistic language of cyberfeminist artist Mare Tralla. This language is characterised by the use of her own body image and by the combination of stereotypically 'feminine' attributes, themes and colours into a critical whole which laughs at and 'against' those gendered stereotypes and hierarchies.

This language functions often as a knife, cutting into the painful social boils that polite use of words or images cannot achieve: for instance, in the exhibition Freedom of Choice, dedicated to the Estonian independence day, the artist showed a photo installation Estonian Beauty (1998), which pointed at the products of patriarchal early capitalist society - trafficking, prostitution and the fact that most of the sex workers active in rich Scandinavian countries come from relatively poorer Estonia.

The artist had first used similarly shocking artistic language in the process of forming her own media image - a process which included numerous outrageous interviews, TV appearances and also performance art. Amongst the latter, Kiss (1996), which reflects on internal and gendered hierarchies in the local art world, is worth a mention.

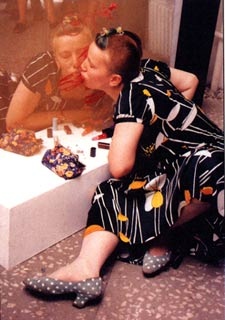

Kiss, performance, 1996

In this performance, the artist faced a mirror-screen projection of video images of Estonian male critics voicing their opinions of Mare Tralla. This functioned almost like a reversal of Virginia Woolf's famous quote from The Room of One's Own: 'Women have served all these centuries as looking-glasses possessing the magic and delicious power of reflecting the figure of man at twice its natural size'. Now it was the men's turn to perform the function of the looking-glass and the artist treated them accordingly: those who praised her were rewarded with a kiss and those who did not were hit with a lipstick.

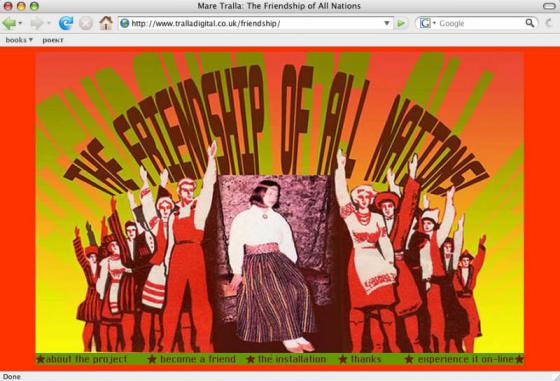

As it has been mentioned, the visual language of her works is quite idiosyncratic within Estonian art: it is influenced by cyber and popular culture, both by 'high' avant-garde and 'low' decorative arts. For instance, an interactive installation eyeBlimp (1999), exhibited during the international new media festival Interstanding 3 in Tallinn and on VideoPositive 2000 in Liverpool, was a hand-made silicone ball hanging in the air and 'communicating' to viewers through a screen on its surface. The only 'desire' of the pink coloured ball was to be touched and caressed as a result of which it recorded the image of the viewer and projected it on its surface screen. A similar combination of high tech and handicrafts was used later in the installation entitled The friendship of all nations (2005), which was part of the show [prologue]: New Feminism/New Europe at Manchester Cornerhouse, introducing various artistic feminisms from the New Europe 4.

The friendship of all nations, 2005

Similar to her earlier works, this interactive and movable installation recalled memories from the Soviet period concentrating on the ideology, rhetoric and practices of multinationalism within the Soviet empire. These practices included the compulsory learning of folk songs of the 'fraternal nations' which were then performed during various music festivals. The installation, built on the repertoire of folk and popular songs from different cultures and in different languages, was simultaneously located in two spaces: in the Cornerhouse viewers were invited to choose between several soft-material colourful balls and walk around with them in the gallery whilst listening to already recorded versions of some songs which were played in these funny 'radios'; the other part of the work was/is located on the internet where all users can continue to contribute towards the piece by sending a song or two.

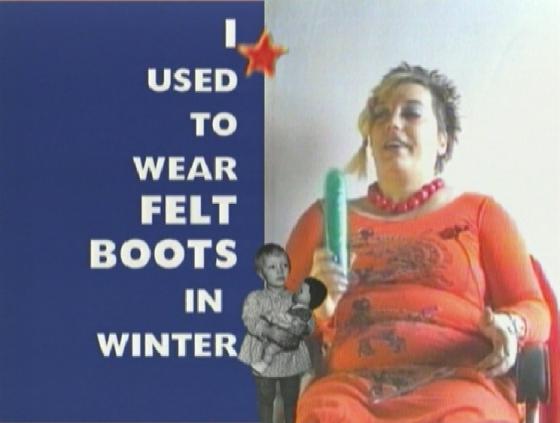

This piece leads us into that characteristic 'Mare-Tralla-world' which can be decoded and shared best by someone who shares the experience of a specific culture, space and time, with the artist: I would claim that the 'ideal' viewer/user of her art is an Estonian who has lived during the so-called stagnation period of the 1980s' Soviet Union. This world and especially its particular ways of resistance are aptly summarised by a video piece Feltboots (2000) which is based on a joke from the non-existent 'Armenian radio' - a collection of anti-Soviet (sometimes anti-Russian) anecdotes widely circulated throughout the SU.

Feltboots, video, 2000

The anecdote asks: why do Russians wear the felt boots? The answer is: well, they do so in order to silently take over the Americans5. In the video, the artist herself dressed in felt boots and stereotypical Russian scarf is trying to literally perform such an action - quietly and unnoticeably to take over the American citizens walking on the city streets in Ohio.

Feltboots, video, 2000

Although a specifically coded work of art, which is more easily read by the post-Soviet and post-socialist viewers, it displays an almost vulgar comic attitude characteristic to much of the vernacular culture and as such attempts to relate to much wider audiences.

Trans/nationalism

Mare Tralla has been amongst the most consistent users of 'Estonian woman as a sign' in contemporary Estonian art. Her project to demolish the identity construction of national femininity borrows signs, characters and attributes from different ideologies that have shaped the society of 1990s' Estonia. Works such as the CD-ROM her.space (1996-1998) or the video installation So We Gave Birth to Estonian Feminism (1995) present female imagery relating to three different realities which have influenced the identities of Estonian women during the past decade or so - the residues of the Soviet period, the ideals of nationalist nostalgia and the global ideology of capitalist consumer society.

The artist, herself to some extent a product of the 1980s national awakening movement, does not try to hide the importance of nationalist ideas in the identity formation of young women of her generation. In one interview she described how the myth of powerful Estonian women, widely spread both in literature and popular folklore, offered her an opportunity to identify herself with an image of a strong, powerful Estonian woman6. Quite naturally, such an identity construction was limited to a romanticised and nationalist image: Mare recalls having worn the stripy skirt of a national costume, collecting herbs in the forest and doing housework as befit to a true Estonian, i.e. non-Soviet woman. Thus the multiple appearance of the figure of a girl wearing a folk costume - a white blouse and a stripy skirt, functions both as an autobiographical document and as the symbol of the concrete era of new national awakening.

her.space, CD-ROM, 1996-1998

The CD-ROM her.space is perhaps the best example of this. The piece pays particular attention to constructions of ideal femininity in the Soviet regime such as heroines of socialist labour and women cosmonauts; these the artist frequently juxtaposes with the images of femininity wide-spread in the Western/global media and popular culture and those currently in the making within Estonian society. her.space does not attempt to draw a self-portrait of the author nor her autobiography, rather it is a presentation of the identity of the Estonian woman as it is constructed historically through different ideologies and ideals. It has been shown that 'woman as sign' has little to do with an experienced or imagined female existence and this is why her.space is built up as a labyrinth of contradictory signifiers instead of trying to present any coherent identity.

her.space, CD-ROM, 1996-1998

In this work, the artist also documents the early reactions of Estonian women to feminism - the discourse which entered local debates in the beginning of the 1990s, concluding that this reaction was shaped as much by the experiences of the Soviet-type equality, limited to a work-place and subjugated to the needs of the state, as by contemporary media-driven or nationalist trends of antifeminism. Austrian curator Yvonne Volkart has described the formation of female identity presented in her.space as 'an arbitrary, system-dependent line-up of various, significant episodes, which have common structure despite their differences'. According to her, the CD leaves no doubt about every identity being 'a sequence of ideological constructions, from which there is no escape' except through the use of irony7.

Sing with me, video installation, 2000

The interactive video installation Sing with Me (2000) functions in a similar manner: it makes playful use of the symbol of Estonian national independence - the Song Festival - and of the imagery of national femininity. In this work, the spectator is faced with an image of the female character, played by the artist herself, who is dressed in a swimming suit and cap, red leggings and running shoes and is located on the stage where the biggest Song Festivals take place. The viewer is asked to sing something into the microphone next to the screen in order to make a 'folk singer' on the screen sing; if she did, the image of a strangely dressed woman responded by singing in an exaggerated operatic manner one of the most popular songs from the 19th century nationalist awakening period, the song which is known and has been used as a popular party song to the present day.

Sing with me, video installation, 2000

The works of Mare Tralla are characterised by the fact that they always draw our attention to the problematic of representation in contemporary visual culture: in the process of looking, the gap between representation and the reality, the sign and the subject, i.e. in the case of the above discussed works the gap between the stereotype of the national woman and actual women's realities, is being revealed. The artist makes use of stereotypes of national femininity, but they are presented in a slightly distorted, exaggerated or ironical way in order to make visible the ideology which underlies them.

In Sing with me, for instance, the digitally manipulated image of the singer in a swimming suit, performed by the uncontrollable female body and voice, results in a parody of traditional images of signing women in Estonian culture. This grotesque yet funny character is created in order to evoke laughter and allow the spectator to laugh at the official forms of performing and re-creating officially endorsed national identity. We should not forget that Mare had, during the 1980s, created her identity as an Estonian, nationally-minded woman, thus, it becomes clear that she does not laugh only at the prescriptive practices of nationalist ideology but also at her own past as characterised by nationalist fervour.

Laughter

Anyone thinking about Mare Tralla's art cannot avoid asking the following question: How can an artist who positions herself as a joker generate a constructive and critical laughter targeted at the surrounding society? First of all, one should remember that the relationship between the artist and the spectator(s)/society is built in her art similarly to the typical relationship between the joker and the court: the joker seemingly makes himself the target of the court's laughter and the court may not notice that actually they laugh at themselves. The central place of laughter in Mare's art serves a particular purpose - something which can be best described using Walter Benjamin's words: nothing stimulates the process of thinking better than laughter.

Many theorists have foregrounded the significant role played by irony, self-irony, grotesque, vulgar folklore and other types of comic culture in feminist and cyberfeminist art which aims to critique cultural stereotypes and traditional modes of representation of gender8Rosi Braidotti has called this strategy 'the politics of parody' or 'parodic repetition' which being grounded and sustaining a political effect, can provide a politically empowering position9. However, in the case of Estonian (women's) art this strategy has an immediate and important relation to a more local history of satire, (self-)irony and laughter in the Soviet and East European culture, which all functioned to bypass the ideologically rigid rules of the production of culture as well as to soften the absurdity and/or repressive nature of a socialist reality.

Mare's art functions precisely as some sort of carnivalesque. At least for a moment, her works manage to turn the dominant (patriarchal) order upside-down as well as to question our and her own positioning with regard to this dominant order. I do not think that a self-critical and self-ironic dimension, so prevalent in most of her works, would diminish the constructive and empowering potential of her art. The laughter does not speak in a dominant language, although it may be forced to use the expressions of this language and is necessarily located within the dominant symbolic order. Mare's art belongs to these artistic practices which always leave the spectator with an impulse for critical thinking.

- 1. The article was originally written for the following publication: Estonian Artists 3. Ed. A. Trossek. Tallinn: Center for Contemporary Arts, Estonia, 2007.

- 2. http://old.artun.ee/~mare/kmm.html

- 3.

- 4. http://www.tralladigital.co.uk/friendship/

- 5. This anecdote refers to the slogan of the post-Stalinist Soviet-type modernization launched in the late 1950s which sounded roughly as follows: 'We will catch up with the Americans, take over and leave them behind', i.e. create a technologically, industrially and economically more advanced society than the US was.

- 6. Pauline van Mourik Broekman, State of Play. An Interview with Mare Tralla. In Private Views: Spaces and Gender in Contemporary Art from Britain and Estonia. Eds. A. Dimitrikaki et al. London: Women's Art Library, 2000, p. 22.

- 7. Yvonne Volkart, Connective Identities. In: Double Life: Identity and Transformation in Contemporary Art, ex. cat. Vienna: Generali Foundation, 2001, p. 61.

- 8. See for instance: Jo Anna Isaak, Feminism and Contemporary Art: The Revolutionary Power of Women's Laughter. London, New York: Routledge, 1996.

- 9. Rosi Braidotti, Cyberfeminism with a Difference. In: Feminisms. Eds. S. Kemp, J. Squires. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 1997, p. 525.